The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on malaria control and elimination efforts. Modeling predictions suggested the annual malaria death toll in sub-Saharan Africa could double because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) urged countries not to scale back their planned malaria prevention, diagnostic, and treatment activities during the COVID-19 pandemic; otherwise the gains made in saving lives from malaria and other diseases over the past 20 years may be lost.

Prompt care-seeking for fever is critical for malaria treatment, as it can help prevent severe disease and death. In the wake of the pandemic, community members received mixed messages and were unclear whether they should seek immediate care for any and all fevers or self-isolate at home per the guidance for fevers in the context of COVID-19. Communities presumed that health facilities were closed for malaria testing or could be COVID-19 infection hubs. Some were hesitant to visit facilities due to fear of testing positive for COVID-19 and be quarantined, potentially at their own expense. Several countries also imposed physical distancing rules, which prevented interactive community events and in-person malaria social and behavior change (SBC) opportunities.

Malaria SBC programs had to think afresh and re-strategize to tackle new limitations to reach audiences and convince them to change their behaviors to prevent and manage malaria. Malaria SBC workers increased their efforts while also closely following COVID-19 guidelines. These are just a few of their stories.

Ethiopia: Call of the Trumpet

This Ethiopia case study offers insight into leveraging community members’ existing social capital to reinforce insecticide-treated net (ITN) use and prompt care-seeking for fever during COVID-19. They literally blew trumpets to drive home their messages.

Nigeria: The Mobile Classroom

This case study from Nigeria showcases the ability to innovate and build the SBC capacity of field staff with limited resources. It demonstrates that even simple technologies like interactive voice response can provide practical solutions during a crisis.

Cambodia: Inside the Jungle

The Cambodia case study reveals the benefits of long-term investments in community structures and the importance of local ownership and SBC capacity to reach the country’s hardest-to-reach communities.

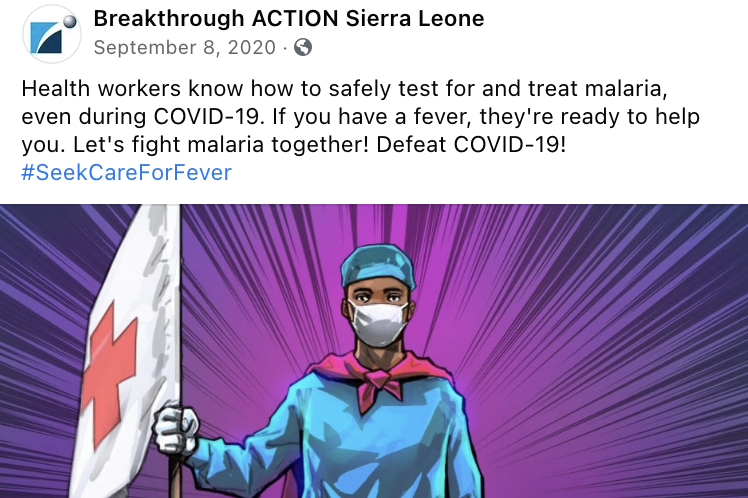

Multi-Country: Click, Share, Engage

This snapshot of social media case studies from India, Guyana, Angola, and nine other sub-Saharan African countries flags both the potential and the challenges of using the favored “tech” approach for SBC.

Lessons Learned

While each case study shares specific lessons learned, a few lessons are cross-cutting learnings:

- Community leadership is the key to crisis mitigation. Creating local ownership, sharing SBC skills, and offering appropriate technical resources lays the foundation of trust and presence for malaria programs in communities. These community platforms have proven to be resilient and can be quickly leveraged – even remotely – in times of crisis.

- Malaria SBC projects that engaged and coordinated with the national and subnational COVID-19 task forces delivered safe and effective implementation. Integrated approaches ensured complementary malaria and COVID-19 key messages, removing confusion about when and how to seek health care services.

- In a crisis, perfection is not mandatory, but prompt action is. Innovativeness, using existing structures, and quick action allowed for new impact and the avoidance of no impact at all.

- Flexible budgets were key to the success of programs because they allowed programs to modify approaches easily and quickly to best meet the unique needs of the pandemic, including transitioning to virtual, remote, or mobile approaches.

- Unlikely partnerships, such as engaging the Ministry of Environment and Forests in Cambodia in malaria prevention and testing, have sustained impact even throughout pandemic restrictions. Similarly, public-private partnerships can quickly emerge or be leveraged, such as mobile phone networks, to communicate when face-to-face interactions are not possible.

- While social media does not reach all communities at risk for malaria, it can help amplify existing messages and project goals. During a crisis, it can allow for a wide reach, especially at a time when people may turn to mobile phones more frequently for information.

Malaria Materials during COVID-19

In addition to the projects showcased, many projects sent malaria SBC materials created in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Please note, the rights to these media resources belong to their respective projects.

Cover photo by USAID StopPalu+.

Date of Publication: April 20, 2022