Moyo ndi Mpamba, Usamalireni! (“Life is precious, take care of it!”) was an aspirational campaign that connected the idea of wellness to prosperity, and encouraged Malawians to take steps to improve their own health and that of their families.

The messages promoted by the campaign included both straightforward health information, as well as a multitude of examples to emulate in the form of success stories that came straight from the communities where the campaign was implemented. This was achieved through the coordinated implementation of a variety of communication activities including multiple radio programs, community outreach and mobilization, and family-friendly print materials.

The Moyo ndi Mpamba campaign was a unifying umbrella brand implemented under the Support for Service Delivery Integration (SSDI)-Communication project. SSDI-Communication sought to encourage behavior change in families and communities, and stimulate demand for services in six key health areas: family planning, malaria, maternal and child health, nutrition, water and sanitation, and HIV. The project was implemented by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (CCP) in partnership with Save the Children International, the Malawi Ministry of Health, and multiple local partners.

Timeline

Inquire

Before the design and launch of the campaign, the SSDI-Communication team carefully reviewed existing data and surveys, and conducted both a baseline quantitative research study, and a formative qualitative research study.

A Malawi Demographic and Health Survey and a Malawi Malaria Indicator Survey had recently been conducted, in 2010. From these surveys, it was clear that though health and development indicators in Malawi were improving, there was still a long way to go to drastically reduce unacceptably high levels of disease and premature death. Maternal, infant and child mortality was declining but remained at high levels overall (675 maternal and 133 under-five deaths per live births per 100,000 live births). Malaria remained endemic, with 6 million episodes throughout the country annually. Malnutrition had declined, but remained a major problem, with 47% of children stunted, and 63% anemic.

SSDI-Communication’s baseline quantitative survey revealed several key pieces of information that informed the design of the campaign. A summary of key findings includes:

- Overall high levels of knowledge related to the six focal health areas of the project

- Overwhelming approval of family planning, and social norms conducive to the uptake of family planning

- High levels of self-efficacy around breastfeeding and the use of bed nets

- Low rates of knowledge around danger signs in pregnancy and young children

- Beliefs and norms not conducive to key HIV prevention related to circumcision and condom use

- High rates of self-reported performance of key health behaviors, including hand washing after certain key moments, family planning and contraception use, bet net use, and health seeking behavior upon onset of fever

- High rates of gender norms conducive to joint decision making and condom negotiation

- Low rates of couple communication regarding health issues and behaviors, including HIV and family planning

This information provided essential insight into which health messages to promote, and which aspects related to behavior change – such as self-efficacy, couple communication, attitudes, social norms – needed to be addressed throughout the campaign for each specific health topic and behavior.

Read the full baseline report.

SSDI-Communication’s formative qualitative research focused on understanding Malawian men’s and women’s perceptions of “health,” and what it means to have a “healthy family.” Key findings from this research included:

- Attributes of a healthy family, as perceived by Malawians:

- Small family with mother, father, and two children

- Happy, well-nourished and well-dressed

- Well-built, clean house with windows, a front door, a clean fenced yard, trees, a clothes line, separate rooms, and a plot for farming

- Attributes of an unhealthy family, as perceived by Malawians:

- Many children (6 or 7), malnourished and poorly dressed

- Live in a mud hut with a thatched roof

- Open defecation occurs, and animals live alongside family members

The insights gained from this formative research were vital to the creation of the Moyo ndi Mpamba campaign brand, slogan, visual look, and overall feel.

Read the full formative research report.

Additionally, research from both studies showed that the main sources of information on health were health care providers, community and district health workers, and radio, as well as village chiefs and community dramas.

- Baseline Survey of 15 Districts in Malawi, 2012

- Perceptions Regarding Healthy and Unhealthy Families: Formative Research Findings, Malawi

Design your Strategy

SSDI-Communication was designed based on the Social Ecological Framework, which posits that individual, household, social network, community, and national factors affect the health and wellbeing of community members by influencing, directly or indirectly, families’ and individuals’ ability or propensity to act.

The project also used a life-stage approach. This enabled health communication and promotion efforts to be targeted and prioritized around what is most relevant to people at various points in their lives. Audiences were categorized in four major life stages:

- Young married couples

- Parents of children under five

- Parents of older children

- Adolescents

These two strategic approaches, the social ecological framework and the life stages approach, were also incorporated into the campaign strategy.

Because the available data and research showed a high awareness among audiences on all six health topics that were the focus of SSDI-Communication, the central strategic approach for the campaign was to create a positive and enabling environment for men and women, health workers, religious and community leaders. In this environment they would be able to actively discuss health problems and issues, find ways to tackle them together and then take actions to change individual behaviors and community norms.

The positioning for this campaign reflected the audiences’ understanding of health and wellbeing: packaging messages and images under a healthy lifestyle brand, using positive images of audience representatives living out the aspirations of everyday Malawian people: small healthy families doing simple things to keep healthy.

The campaign aimed to offer audiences hope and confidence that they can change, just like other people are changing. The strategy specifically aimed to acknowledge and celebrate the changes that people were already making.

The brand and campaign ensured the incorporation of key messages and the overall creative concept, which is described below, by:

- Unifying all campaign communications and interventions.

- Ensuring coherence and continuity.

- Integrating approaches that addressed a wide spectrum of health topics simultaneously over a prolonged period.

The campaign included mass media activities, which had a national reach. Key print materials for family and community use supported district and community-level activities led by sister project SSDI-Services. Support for community mobilization and other community-level activities ensured the incorporation of key messages and the Moyo ndi Mpamba concept.

Create and Test

During a participatory workshop, several concepts for the overarching concept for the campaign were developed based on the gathered research, overall strategic approach, and local knowledge.

| Big Idea | Supporting Ideas |

| It’s Good (Zilibwino) | How about you? (Nanga inu)You too can (Nanunso mungathe) |

| Life is Capital/Precious (Moyo ndi Mpamba) | Take care of it (Usamalireni)Prune it (Utengulereni)Nurture it (Uchengetereni) |

| On the right track (Zagwira nsewu) | Keep going/keep moving (Yendandibe/Tiyeni nazo) |

Two of those concepts (Zilibwino and Moyo ndi Mpamba) were tested with members of the campaign’s intended audiences, and the winning concept was Moyo ndi Mpamba, Usamalireni! – “Life Is Precious, Take Care of It!” was an almost unanimous choice for pretesting participants. They noted that the brand name and slogan was easy to understand and relate to the idea of business capital that must be looked after very well at all times to ensure the success of an ongoing business venture. This was interpreted to mean that one’s life and health must be looked after very well to ensure prosperity. Pretest participants felt that “Zilibwino” (“It’s good”) was too general to work well with audiences of all life stages.

The project developed and pretested several versions of logos that aligned with the overall Moyo ndi Mpamba concept. The logo options included the brand and slogan, surrounding a hand holding a family (2 parents and a child) within a heart.

Ultimately, the logo shown was chosen. Pretesting revealed that audience members felt that the logo showed:

- The words in a complete circle represented a new life and protection around it

- A message prompting one to take care of their own lives

- That taking care of life and one’s health is in their hands, as the hand is carrying the people

- A family doing things together

- Love

SSDI-Communication produced a series of mass media materials – radio spots, posters, billboards – to promote brand recognition and introduce topline key health messages to the public, which were pretested before being finalized and launched.

Mobilize and Monitor

Mobilization

SSDI-Communication rolled out the Moyo ndi Mpamba campaign in two phases:

Phase 1: For 12 weeks, SSDI-Communication introduced the “Life is Precious: Take care of it” concept and brand, through high profile national and zonal launches, the dissemination of Moyo ndi Mpamba songs by popular artists, radio spots, billboards, posters, branded t-shirts, and branded chitenje (cloth wraps).

Phase 2: Through a mix of media, SSDI-Communication disseminated malaria, sanitation, MNCH, family planning, HIV, and nutrition messages. All messaging was branded with the Moyo ndi Mpamba slogan and logo and directed audiences to health facilities and community health workers for further information and services.

SSDI-Communication created a series of materials that promoted brand recognition and topline key health messages to the public:

- Billboards, placed in locations with high traffic

- Posters

- Pamphlets

- Radio Spots

The project implemented a series of other Moyo ndi Mpamba-themed mass media interventions that integrated health messaging from all six health topics addressed by SSDI-Communication:

- Radio programs: A radio serial drama and a reality radio show, both named and themed based on Moyo ndi Mpamba, promoted healthy living while engaging audiences emotionally and soliciting their feedback.

- National dialogues: Radio stations were trained on how to discuss health topics in their popular programs, and the entire country talked about Moyo ndi Mpamba for 5 full weeks, once in 2014, and once in 2016.

- Music4Life: A music album, music video, and a series of music concerts promoted key health messages while providing high quality entertainment.

Finally, the project supported the creation of various integrated SBCC tools for use at the household and community level.

- Family Health Booklet: This highly visual integrated SBCC tool brought key health messages across 6 health areas into the homes of families.

- Community Health Worker Flipchart: This flipchart integrated health messages across 6 health areas in an easy-to-use format for community health workers and volunteers, to facilitate group discussions and dialogues with families.

- Marriage counseling and newlyweds booklet: Religious leaders were trained in how to incorporate health messages into marriage counseling sessions, while newlywed couples were given booklets full of messages vital to their life stage.

Messages throughout all of these interventions aligned to the overall SBCC strategy, and all materials were branded with Moyo ndi Mpamba. This contributed to consistency, continuity, and massive brand recognition.

Monitoring

Throughout the implementation of activities, SSDI-Communication conducted a variety of monitoring activities:

- The team monitored airwaves to see how many times Moyo ndi Mpamba radio spots and radio programs aired

- Trips to the districts confirmed that posters, billboards, and leaflets were in place and disseminated

- Supportive supervision visits to CAGs provided opportunities to learn how many community mobilization activities were ongoing

- Collaboration with SSDI-Services allowed staff to track how many Family Health Booklets and Community Health Worker Flipcharts were disseminated

Additionally, SMS received during the airing of the Moyo ndi Mpamba radio serial drama as well as the Moyo ndi Mpamba reality radio program served as vital monitoring and feedback data. These messages provided valuable insight into how audiences received the programs, and how future episodes could be adjusted to better meet their needs.

SSDI also organized quarterly review and re-planning meetings in each District and nationally. These meetings included staff not only from SSDI-Communication but also the MOH and other partners. During these meetings, community volunteers and service providers shared service statistics and feedback from their discussions with audience representatives. SSDI-Communication used these inputs to adjust plans going forward.

A large number of success stories were collected and documented thanks to reports made by community mobilization volunteers, and individuals who contacted SSDI-Communication via SMS through its two radio programs.

- Read the SSDI-Communication success stories booklet

- Read the SSDI-Communication end-of-project report

- View the SSDI-Communication online toolkit

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Billboards

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Posters

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Leaflets

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Radio Spots

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Family Health Booklet

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Community Health Worker Flipchart

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Marriage Counseling for Newlyweds Training Manual

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign Malaria Comic Book

- Malawi – Moyo ndi Mpamba Reality Radio Program

- Moyo ndi Mpamba Malawi Music4Life All Stars Music Album

- Malawi: Moyo ndi Mpamba All Stars Music Video

- Moyo ndi Mpamba Campaign

Evaluate and Evolve

SSDI-Communication conducted an endline survey that mirrored the methodology and focus of its baseline survey. These two surveys allowed research staff to evaluate what impact the Moyo ndi Mpamba campaign has had. Key findings from the evaluation include:

Exposure to Moyo Ndi Mpamba

- Seventy-eight percent of men and 71% of women were exposed to at least one Moyo ndi Mpamba campaign activity

- Men were exposed to significantly more campaign activities than women

- More people in general were exposed to the radio program than the community or face-to-face activities

WASH

- Nearly 70% of all exposed respondents reported that they wash their hands using soap and water at endline compared to 57% during the baseline. (The percent of non-exposed respondents who reported behavior was slightly lower than the overall rate at baseline.) Additionally, there was a considerable decrease in those who reported only using water (41% at baseline and 28% at endline).

- Compared to non-exposed participants, exposed participants were significantly more likely to report washing their hands with soap and water and less likely to report using water only.

Malaria

- At endline, under-five children living in households exposed to the program were more likely (92%) than those who were not exposed (84%) to sleep under a bed net the night prior to the survey.

- Of mothers who reported sleeping under a bed net, 91% at endline compared to 83% at baseline reported using an insecticide-treated net.

Fertility Preferences and Contraception

- Exposure to the campaign was associated with greater likelihood of currently using any form or a modern form of contraception for both men and women

- 45% of the population who were not currently pregnant or trying to get pregnant reported currently using modern contraception.

- Exposure to a family planning message from at least one activity from the campaign was associated with increased family planning intention among both men and women.

- Among current non-users of contraception, 81% of men and 69% of women intend to use contraception in the future.

- Women who were exposed to at least one campaign activity were significantly more likely to desire fewer children.

Maternal and Child Health

- Among women with a child ≤5 years old, 98% reported receiving antenatal care during their pregnancy.

- The mean number of ANC visits varied by Moyo ndi Mpamba participation or exposure: while non-participants reported an average of 3.1 visits, Moyo ndi Mpamba participants reported an average of 3.4 ANC visits, a statistically significant difference.

- Program participants were significantly more likely to use any bed net as well as more likely to use LLINs every night during their most recent pregnancy.

- Compared to baseline, a larger percentage of women at endline reported giving birth with the aide of a trained medical attendant, and that a physician or clinical officer attended their birth. There were no differences by program participation.

HIV & AIDS

- 35% of all respondents indicated that they had talked to at least one other person about HIV/AIDs topics compared with 44% at baseline. While endline rates were lower, exposure to the program was positively and significantly associated with such conversations.

- Just below 90% of women and 82% of men sampled reported being tested for HIV compared to two-thirds at baseline.

- Exposure to the program was significantly and positively associated with HIV testing (women: 79% unexposed vs. 93% exposed; men: 72% unexposed vs. 85% exposed).

Sexual Behavior

- 21% of the total sample reported having more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months

- Exposure to at least one campaign activity was associated with significantly reduced likelihood of having more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months.

- Overall, 14% of respondents reported using a condom at last sex.

- Exposure was not significantly associated with condom use at last sex.

- Women who were exposed to Moyo ndi Mpamba were significantly more likely to perceive that some/most of their peers would approve of their consistent condom use. There was no significant effect of exposure among men.

Gender Norms

- Exposure was associated with significantly higher gender equitable beliefs among both men and women.

- Program participants (both men and women) were more likely than non-participants to report greater levels of joint decision-making.

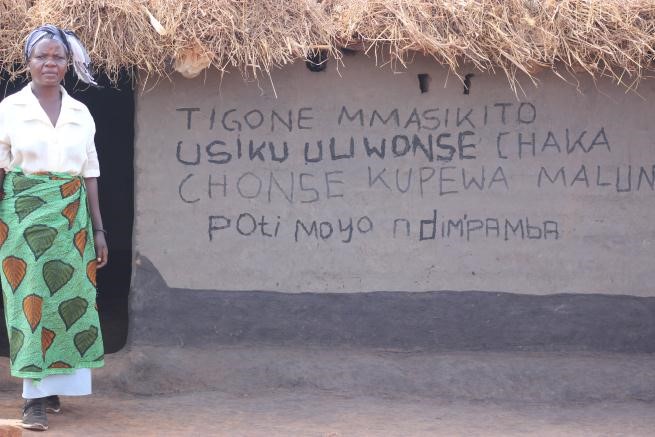

Anecdotal reports indicate that the campaign has permeated the consciousness of Malawians, and the words “moyo ndi mpamba” are commonplace in daily conversations. The slogan “Life is Precious: Take care of it” is widely used in the media. It is even displayed on homemade signs and written on houses. See the photo in this section for an excellent example of homemade signs – which says “Let’s sleep under a net every night throughout the year to prevent malaria – Life is precious”. Feedback from communities and radio listeners indicate that the campaign has successfully reached and inspired discussion about the essential health practices it promotes. The Family Health Booklet is a treasured resource that will be used for years to come by families and communities, who view the booklet as a valuable tool they can use to improve their lives.

The wild success of the brand and campaign will likely translate into a boost for future SBCC campaigns that adopt the slogan. Additionally, the Malawi Ministry of Health has dictated that all health programs implemented in collaboration with the government should bear the Moyo ndi Mpamba logo and brand. The Ministry formalized this decision in the 2015-2020 Malawi National Health Communication Strategy.

- Malawi National Health Communication Strategy, 2015-2020

- Malawi Moyo ndi Mpamba : Findings from the 2016 Endline Survey of 15 Districts

Lessons Learned

- Designing an integrated health communication strategy, agreeing on the life stage audiences and key health practices for each, takes time. Each health sector needs to buy in and feel a part of the campaign, so there are many reviews and revisions before it is final.

- The process for designing an integrated campaign needs to be inclusive, involving stakeholders from all sectors so they buy-in and feel the campaign is their own. Otherwise, there is the danger that they will implement competing campaigns that confuse audiences.

- There are cost savings from integrating health communication where possible, rather than training community volunteers separately on each issue, preparing support materials separately for each individual issue, and developing radio programs on separate health issues.

- Creating a widely appealing brand for health promotion that resonated with the priorities and daily lives of Malawians was effective. The dissemination of branded communication through multiple channels, including radio, mid-media, mass media, community events, community mobilization, and print materials ensured a wide reach and high recognition of the brand. Additionally, branding the overall campaign, and imbuing the brand with an overarching value helps build trust and a following. Rather than a health information campaign, it becomes a health “movement”.

- Developing centerpiece materials for life stage audiences allows the flexibility to integrate new health issues as they occur. For example, when there was a cholera outbreak, it was easy to integrate cholera messages into the radio programs and community activities.

- The adolescent audience is unique and needs its own, separate communication channels. Adolescents provided feedback that they felt left out of the campaign.

- Ownership of a radio was statistically significantly related to being exposed to the campaign; over time, men listen to radio significantly more than men. 40% of men and only 5% of women listen to radio every day. This impacted overall exposure to the campaign and its interventions among women. Future projects should work to find ways to reach women more effectively, and/or expand radio ownership and access among women.

- Though many projects implemented in countries with low literacy and grade completion rates shy away from using print materials, SSDI-Communication found that giving print materials to families which included pictures and simple, easy to understand text was empowering and effective. Even among communities where literacy was very low, members of the community that could read would take on the responsibility of ensuring their neighbors were aware of the messages in the booklet.

Banner image: Credit: Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs

Date of Publication: April 20, 2022