Introduction

Developed by Breakthrough RESEARCH, this guide will help managers support research, monitoring, and evaluation (RME) staff and ensure they have the programmatic data required to track results, and it will ensure the program is guided by robust theory-driven evidence with results tracked over time and at program completion. While the steps presented include examples specific to family planning (FP) programs, they can be used for any social and behavior change (SBC) program.

This guide is one of a series of how-to guides on the Compass for SBC that provide step-by-step instructions on how to perform core SBC tasks. From formative research through monitoring and evaluation (M&E), these guides cover each step of the SBC process, offer useful hints, and include important resources and references.

Why use behavioral theories when developing a theory of change to monitor and evaluate SBC programs?

Behavior change theory is used to explain people’s behaviors and the determinants that make it easier or harder to change those behaviors. Behavior change theory should be incorporated into the SBC program theory of change to illustrate how or why a desired change is expected to occur (i.e., the change pathways) and therefore provide guidance on how to measure behavioral determinants that influence program goals and objectives. For more on how to develop a theory of change, see the resources available from the Center for the Theory of Change.

The change pathways reflected in the theory of change should guide development of the M&E plan. An M&E plan for an SBC program outlines a) indicators to measure progress and results following the change pathways, b) methods for how they are going to be collected and monitored, and c) plans for how data will be analyzed and results will be communicated. An M&E plan for an SBC program helps ensure that data will be used efficiently to improve the program and report on results at various intervals.

Who should develop the theory of change for the SBC M&E plan?

The program staff involved in designing and implementing the program should develop the theory of change in collaboration with the RME staff. The RME staff should then use the theory of change to guide development of the SBC M&E plan in consultation with the program staff.

When should the plan be developed?

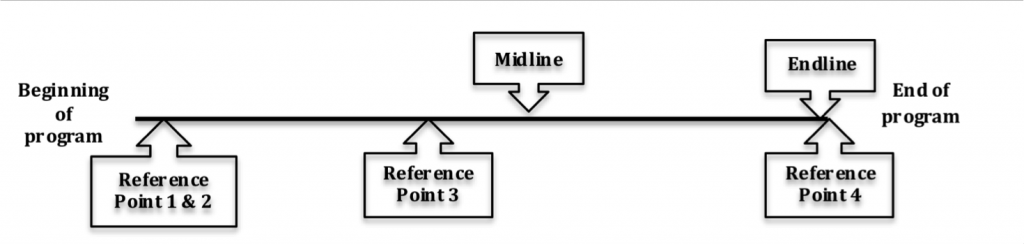

Ideally, an SBC M&E plan guided by the theory of change should be developed at the beginning of the SBC program, when the interventions are being designed. By instituting a system to monitor their program’s progress, programs can periodically reflect and make program adaptations informed by evidence. An SBC M&E plan also enables the program to evaluate success. When this is not possible, it is never too late to work with program staff to develop a theory of change and evaluation plan.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is designed for program managers and midlevel professionals who are not trained as researchers but need to understand the rationale for using a theory-based approach to designing programs and the measurement processes involved. The guide will help managers support RME staff and ensure they have programmatic data required to track results, and it will ensure the program is guided by robust theory-driven evidence with results tracked over time and at program completion. While the steps presented include examples specific to FP programs, they can be used for any SBC program.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the rationale for building a SBC program theory of change that incorporates behavior change theory.

- Identify the types of indicators that are useful to mea- sure in an SBC program through inclusion in an SBC M&E plan as described in “How To Develop a Monitor- ing and Evaluation Plan.”

- Learn how data can help explain whether the SBC program reached the desired outcome or, if not, why not.

Estimated Time Needed

Developing a program theory of change and selecting indicators for an SBC M&E plan can take up to a week, depending on the program’s size or scope, the availability of program and RME staff, and the extent to which staff have considered factors influencing priority behaviors.

Prerequisites

How To Develop a Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

Steps

Step 1: Understand factors influencing priority behaviors targeted by the SBC program using behavioral theory

To develop an SBC M&E plan, program staff, with input from RME staff, must identify the priority behaviors and understand the underlying factors (e.g., financial or distance-related barriers) and/or behavioral determinants (e.g., attitudes and social norms) that the program is targeting to achieve desired change. Several resources are available to help identify priority behaviors, including Advancing Nutrition’s Prioritizing Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Behaviors, the THINK Behavior Integration Guide (BIG), and the Evidence-Based Process for Prioritizing Positive Behaviors for Promotion: Zika Prevention in Latin America and Caribbean and Applicability for Future Health Emergency Responses.

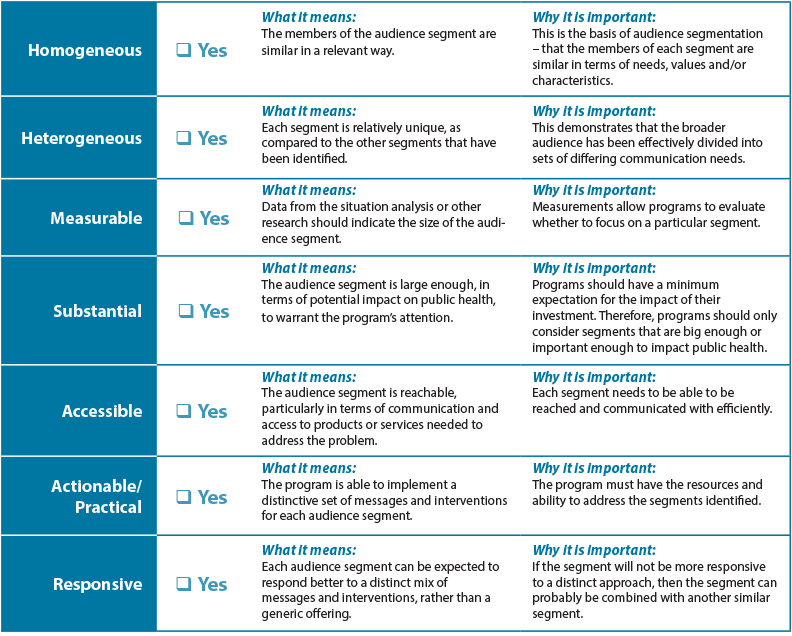

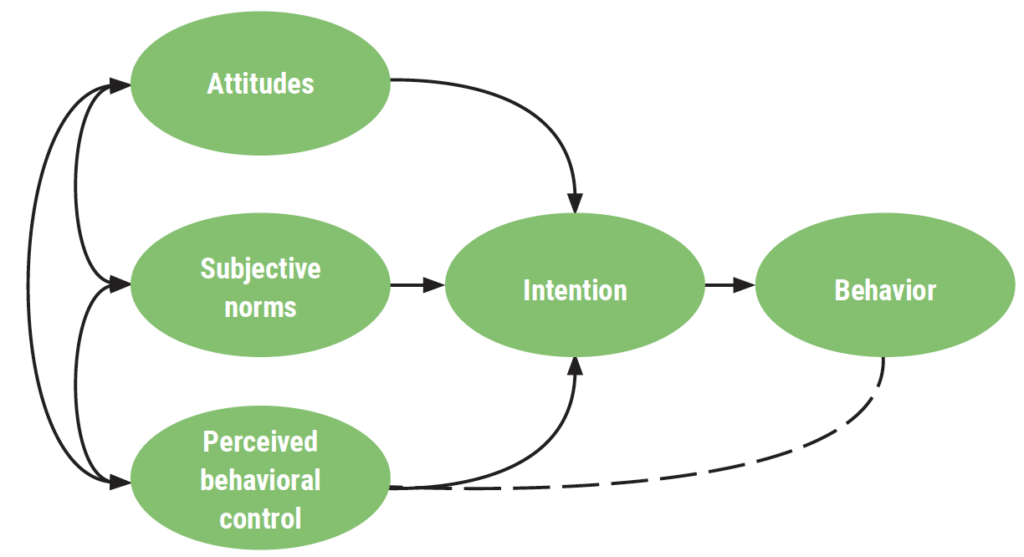

Behavior change theory provides a theoretical foundation for identifying behavioral determinants. There are behavior change theories that are focused on the individual level, such as Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior,1 and multilevel SBC theories, such as the socio-ecological model,2 that explain how behavioral determinants at multiple levels influence health behaviors.

Figure 1 presents Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, which describes how individuals are more likely to adopt a behavior if they have positive attitudes toward the behavior, believe that others in the community support the behavior (or subjective norms), and believe that they have control to adopt the behavior. These determinants influence an individual’s intention to adopt and his or her ultimate behavior adoption.

Table 1 provides definitions and examples of the behavioral concepts described in the theory of planned behavior.

| Behavioral Determinants | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | An individual’s overall evaluation of the behavior | Agree it is acceptable for a couple to use methods such as condoms, the pill, or injectables to delay or avoid pregnancy |

| Subjective norm | A person’s belief about whether significant others think he/she should engage in the behavior | Members of this community would agree if a woman uses contraception |

| Perceived behavioral control | A person’s expectation that performance of the behavior is within his/her control | Agree could use family planning even if his/her partner objected |

| Intention | A person’s motivation to engage in a behavior | Intent to use a modern contraceptive method |

| Behavior | How a person acts or conducts him/herself | Currently using a modern contraceptive method |

Table 1 Behavioral Determinants Definitions and Examples

Figure 2 presents the socio-ecological model. In this model, behavior change is considered in the context of multiple levels, including the individual level; interpersonal level, or relationships with partners, families, and friends; organizational level; community level; and the enabling environment.

Source: Adapted from McLeroy et al. 1988

Program designers may draw from these behavior change theories and/or others to guide development of their program and theory of change. This summary from the World Bank provides an introduction to additional behavior change theories that are commonly used by health programs. Selection of the most appropriate theory is situation-specific and depends on the audience, setting, and behavioral determinants that need to be addressed.

Activities that influence the factors preventing or supporting behavior change

Once the program team identifies the behavioral determinants from behavioral theory that either prevent or support behavior change, they can identify the activities that will influence these behavioral determinants. The list of activities can then be organized in a logical framework, also called a logframe. A logframe is a planning tool that consists of a matrix showing a project’s goal, activities, and anticipated results. The structure helps program designers specify the components of a project and its activities and how they relate to one another. See How to Develop a Logic Model.

Step 2: Build a program theory of change

A program theory of change explains the behavioral determinants that prevent or facilitate behavior change that the program must address to achieve its desired outcomes. Behavior change theories can help to map out the “missing middle,” or the change that program activities bring about in pursuit of its goals.

The program team can develop a common understanding of activities that influence the behavioral determinants preventing or supporting behavior change that can be pursued to bring about desired change in specific behaviors.

Identifying the behavioral determinants also highlights opportunities for measurement in the SBC M&E plan. Thus, the program team can focus not only on the ultimate adoption of a behavior but also consider revising the intermediate outcomes referenced in the theory of change if improvements in behaviors are not seen during or at the end of the project.

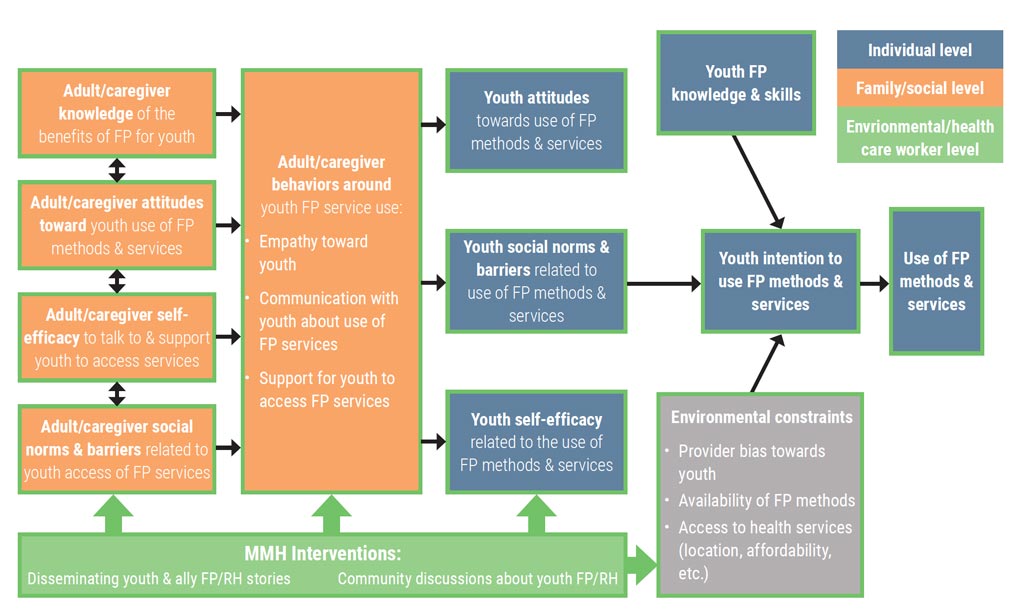

What does a theory of change look like? In the example in Figure 3, the Merci Mon Héros campaign, a youth-led multimedia campaign in francophone Africa, the program’s theory of change incorporates aspects of a behavior change theory called the Theory of Planned Behavior. As described in Step 1, the theory of planned behavior suggests individuals are more likely to adopt a behavior if they have positive attitudes toward the behavior, believe that others support the behavior, and believe that they have self-efficacy to adopt this behavior.

Source: https://ccp.jhu.edu/2020/03/30/youth-reproductive-health-heroes-francophone

These behavioral determinants then influence an individual’s intention to adopt and his or her ultimate behavior adoption. These behavioral determinants are further described in Table 2. The SBC activities in this campaign focus on strengthening communication between youth and supportive adults to improve knowledge and bring about changes in intermediate outcomes, such as youths’ attitudes, self-efficacy, social norms, FP knowledge and skills, and intention to use FP services.

| Behavior | Knowledge | Attitude | Self-efficacy | Intent | Norms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent/adult ally speaks to youth about FP/reproductive health (RH) | Parent/adult ally recognizes that youth are/can be sexually active | Parents/adult allies accepts/tolerates that youth are sexually active | Parent/adult ally believes other parents accept that youth are/may be sexually active | ||

| Parent/adult ally knows to talk to youth about FP/RH | Parents/adult allies believes they should speak to youth about FP/RH | Parent/adult ally believes they can speak to youth about FP/RH | Parents/adult allies intend to talk to youth about FP/RH | Parent/adult ally believes other parents in the community speak to youth about FP/RH | |

| Parent/adult ally knows that youth need guidance | Parents/adult allies approve of youth using FP | Parent/adult ally believes they can speak to youth about FP | Parent/adult ally believes other parents in the community approve of youth using FP | ||

| Parent/adult ally knows that FP can help youth achieve life goals | Parents/adult allies have a favorable attitude toward young people’s use of FP to help them achieve life goals | ||||

| Youth speak to adults about FP/RH | Youth know that there are adults they can trust to talk about FP/RH | Youth believe they should speak with adults about FP/RH | Youth believe they can speak to adults about FP/RH | Youth intend to speak to adults about FP/RH | Youth believe that other youth speak to adults about FP/RH |

| Youth use FP if sexually active | Youth know about the FP methods | Youth believe they should use FP if sexually active | Youth believe they can use FP if sexually active | Youth intend to use FP if sexually active | Youth believe that other youth use FP if sexually active |

Table 2 Intended Outcomes and Hypothesized Behavioral Pathways

Step 3: Select meaningful SBC indicators

RME staff should collaborate closely with program managers and technical experts to gain a solid understanding of the program’s planned activities before selecting indicators and developing an M&E plan for the SBC program. The monitoring plan should be linked to the theory of change that guides program activities.

SBC-related indicators measure processes and approaches implemented to support the intended audiences to adopt and maintain the recommended behaviors, as outlined in the theory of change.

M&E plans for SBC programs should measure the following:

- Number or percentage of beneficiaries exposed to an intervention

- Factors to be influenced by the planned intervention/activities, such as attitudes, self-efficacy, and subjective norms.

- Desired effect on the audience’s behavior

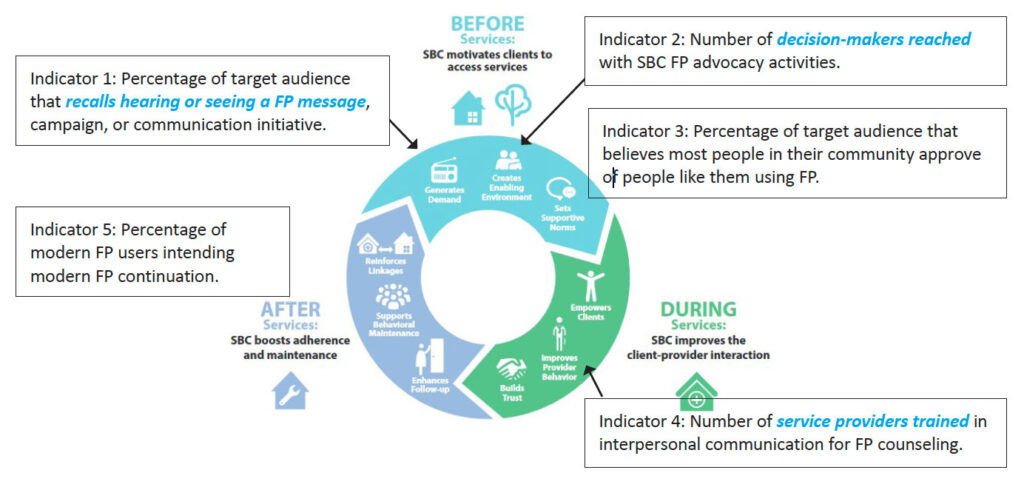

Details on how to measure SBC indicators, including detailed indicator reference sheets, are available to support RME staff in the programmatic research brief Twelve Recommended SBC indicators for Family Planning programs. Several of the indicators detailed in the programmatic research brief can be applied to the stages of the Circle of Care, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Source: Carlsson, O. & Heather, H. 2020. From vision to action: Guidance for implementing the Circle of Care Model. Breakthrough ACTION, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs

In the Before Services stage, a program may create an enabling environment by engaging with decision-makers to gain their support for FP. FP programs also often address social norms. These can be measured by:

- Indicator: Number of decision-makers reached with SBC FP advocacy

- Indicator: Percentage of target audience that believes most people in their community approve of people like them using FP

In the During Services stage, provider behavior is important, and interventions can be used to address client-provider interactions. These can be measured by:

- Indicator: Number of service providers trained in interpersonal communication for FP counseling

- Indicator: Percentage of women who are satisfied with the quality of FP services provided as measured through a client satisfaction score

In the After Services stage, SBC can ensure that people continue to use a contraceptive method. This can be measured by:

- Indicator: Percentage of modern contraceptive users intending to continue using a modern FP method

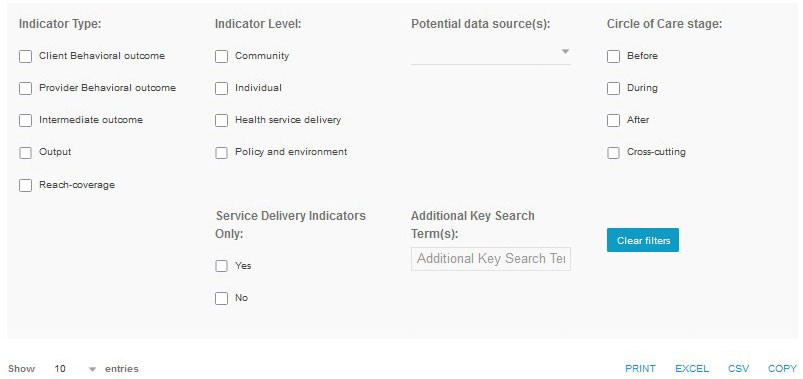

SBC outcomes must be measured to determine whether the behavior has changed as intended. A number of potential SBC indicators are available in the SBC Indicator Bank for Family Planning and Service Delivery (Figure 5). Some examples include:

- Indicator: Percentage of nonusers (among intended audience) who intend to adopt FP in the next 3 months

- Indicator: Number/percentage of women who deliver in a facility and initiate or leave with a modern contraceptive method prior to discharge

Source: https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/social-and-behavior-change-indicator-bank-for-family-planning-and-service-delivery/

This FP indicator bank contains sample indicators for monitoring and evaluating SBC programs. The bank includes a subset of SBC indicators specifically for service delivery.

The data for SBC-related indicators can come from a routine monitoring system that captures outputs such as number of providers trained in high-quality counseling or number of community-level activities for FP conducted in project sites, or they may come from household surveys and qualitative interviews with program participants.

Step 4: Monitor SBC implementation

Measurement is essential to strengthen SBC programmatic focus and determine effectiveness and impact.

Program managers and staff should not wait until the end of a project to find out whether project activities are achieving intended results. When the project is under way, they should start to ask some important questions, including:

- Throughout implementation, are activities adhering to the project design guided by the SBC theory of change? How has the program contributed to an observed intermediate outcome along the theory of change pathways?

- How have contextual factors influenced the intervention?

To answer these questions, RME staff should examine the program’s routine monitoring systems. These would contain the output indicators that capture the project’s completed activities. RME staff can also use targeted qualitative studies to explore how the program is contributing to outcomes along the pathways in the theory of change.

Routine Monitoring

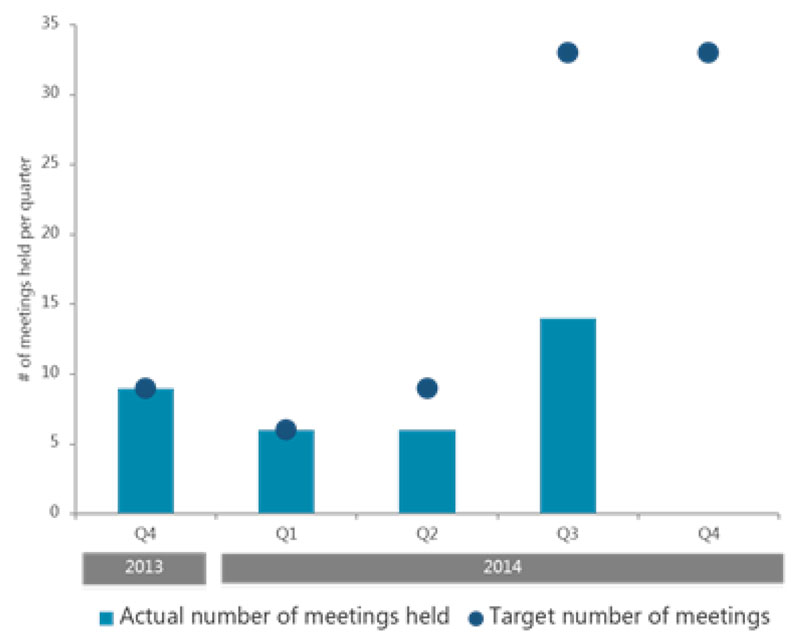

Routine monitoring can uncover gaps between the target and actual number of planned activities. For example, the project may have planned to conduct community meetings to share information with community members.

In Figure 6, the example project met its targets in quarter 4 (Q4) of 2013 and Q1 of 2014 but missed its targets in Q2 and Q3. In the last quarter of 2014, nothing happened, and it will be important to ask why.

It may also be useful to track additional information related to the meetings, such as the number of participants disaggregated by sex or age, to understand who attended the meetings and whether there are any target audiences not being reached.

Source: Dougherty, L. et al.2018. “A mixed-methods evaluation of a community-based behavior change program to improve maternal health outcomes in the upper west region of Ghana,” J Health Commun. 23: 80–90.

Routine monitoring should also track intermediate outcomes related to behavioral determinants so that if improvements are not observed, midcourse corrections can be made. An example of how behavioral determinants can be monitored throughout a program is illustrated through the Confiance Totale campaign.

The Confiance Totale campaign promotes safe and effective FP within a supportive social context in Côte d’Ivoire with the objective of increasing demand for FP services. Breakthrough RESEARCH conducted a monitoring study using interviewer-administered computer-assisted telephone surveys to determine 1) the level of unprompted recall of the Confiance Totale campaign among target beneficiaries and 2) if recall of the campaign was associated with higher levels of perceptions of FP safety, FP-related social norms, self-efficacy, spousal communication about FP, intention to talk to a partner about FP, intention to seek FP information at a health facility, intention to use FP, and current use of FP methods.

Table 3 shows the behavioral determinants measured during the Confiance Totale campaign in Côte d’Ivoire. As shown in the table, we see that among males’ relationship status (being married or living as married) arises as a significant factor associated with descriptive social norms around FP communication and use in their community. This may indicate that males are most attuned to FP-related social norms when they enter long-term relationships, regardless of age. Findings from the monitoring study recommended the campaign purposefully target unmarried men to highlight the relevance and importance of FP use and promote FP as a concern for both sexes in nonpermanent relationships.

Factors associated with the likelihood of believing that others talk about FP—male responses:

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of CT radio spot recall | ||

| At least once a day | 1.35 | .80–2.28 |

| At least once a week | 1.48 | .88–2.47 |

| Less frequently | 1.46 | .59–3.61 |

| Not at all | — | — |

| Time (data collection week) | 1.09* | 1.01–1.17 |

| Current use of FP | 1.87*** | 1.39–2.51 |

| Talked to a health provider about FP in last month | 1.07 | .67–1.71 |

| Talked to partner about FP in last month | 2.53*** | 1.91–3.36 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–24 | — | — |

| 25–34 | 1.44 | .93–2.23 |

| 35+ | 1.26 | .75–2.14 |

| Married or living with someone as married | 1.76*** | 1.27–2.44 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0 child | — | — |

| 1–2 children | .75 | .53–1.05 |

| 3+ children | .85 | .53–1.35 |

| Level of education | ||

| None | .75 | .30–1.82 |

| Incomplete primary | .73 | .38–1.40 |

| Complete primary | — | — |

| Incomplete secondary | 1.04 | .65–1.66 |

| Complete Secondary | 1.18 | .72–1.96 |

| University | .69 | .43–1.12 |

Table 3 Did the Confiance Totale Campaign Address Social and Gender Norms Related to Using Family Planning?

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Source: Silva, M., K. Edan, and L. Dougherty. 2021. “Monitoring the quality branding campaign Confiance Totale in Côte d’Ivoire,” Breakthrough RESEARCH Technical Report. Washington DC: Population Council.

Qualitative research

Qualitative methods such as focus group discussions and in-depth interviews can be valuable tools to explore how and why program activities are working (or not). Researchers can conduct focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with project staff, government stakeholders, and program participants to understand the factors influencing the project’s ability to adhere to its planned activities and how the program is addressing behavioral determinants such as attitudes and social norms.

For example, qualitative findings exploring how the Merci Mon Héros campaign contributed to changes in communication between parents or adult allies and youth about intimate relationships and FP and RH found that among adolescents, the campaign raised their perception of the importance of communication with adults/parents on sexuality issues. The campaign also encouraged some to initiate conversations with their peers and their parents on these topics. Despite the support and enthusiasm of some participants for communicating more with youth or adults, the study also noted a continued reluctance on the part of many to talk about sexuality, with overarching social norms still acting as barriers to communication. Some adults noted they knew they needed to communicate about FP/RH with their youth but did not do so simply because they did not know how and when to talk about it. Youth indicated that it was easier for adults to talk to young people than it is for young people to talk to adults, as talking about sexuality and FP/RH still has negative connotations. These findings provided valuable information related to the theory of change pathways outlined in Figure 3 and helped to provide guidance on how the Merci Mon Héros campaign should adapt to address the challenges described by program participants.

Step 5: Evaluate SBC implementation effectiveness and impact

Measurement is essential to strengthen the programmatic focus of SBC and determine program effectiveness and impact.

Program managers and staff want to know if they reached the desired outcome identified in the theory of change. Some questions to ask include:

- To what extent did the project (or program) document changes in the behavioral determinants that the intervention targeted?

- To what extent did the project achieve the desired behavior change?

- Was the project cost-effective?

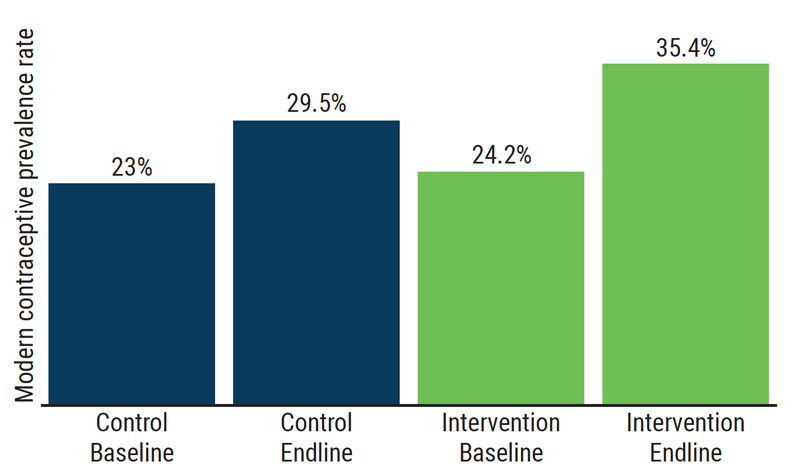

To measure whether a project achieved the desired behavior change quantitatively, managers and staff would need to use routine program and monitoring data or conduct a survey to assess change. Ideally, this survey would measure the behavior before the intervention to establish a baseline value and include a comparison group that is not exposed to the intervention to measure change over time and to ensure that the change occurred because of the intervention. In one example, a mass media campaign in Burkina Faso, the primary outcome of a randomized controlled trial was modern contraceptive use at the time of the survey. Following a 2.5-year campaign, there was a 5.9 percentage point increase in modern contraceptive use in the intervention zones compared to the control zones. Figure 7 illustrates these results. For additional details on impact evaluation designs, please refer to the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Introduction to Impact Evaluation Designs.

Following a 2.5 year mass media campaign, the percent of women who were using or whose partners were using modern contraception increased by 11.4% in the intervention area, compared to just 6.5% in the comparison area.

Source: Glennerster, Rachel, Joanna Murray, and Victor Pouliquen. March 2021. “The media or the message? Experimental evidence on mass media and modern contraception uptake in Burkina Faso” CSAE Working Paper WPS 2021-04. https://www.developmentmedia.net/project/familyplanningrct/#project-impact

Step 6: Communicate findings

A final critical step is ensuring that program results are shared with others who can use the information in their work in formats that are accessible, appropriate, and tailored to the intended audience. Here are a few ways in which findings can be applied to improve programs and disseminated more broadly to key audiences who can take up the findings in their efforts:

- Organize in-depth technical workshops with program team members to discuss emerging findings.

- Discuss evaluation findings with the program’s beneficiaries, seeking their feedback on the validity and accuracy of the findings.

- Provide donors and policymakers with evidence on what works for addressing a given problem, where key gaps exist, and what actions they should consider addressing.

- Publish research results in peer-reviewed journals to reach researchers and technical experts.

- Share through online platforms such as the Compass for SBC and Knowledge SUCCESS to reach program implementers as well as communities of practice (e.g., SBC for service delivery community of practice group).

- Develop policy briefs and fact sheets to reach advocacy organizations and policymakers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This guide describes how to use a theory of change-based approach to design programs and the measurement processes involved. The guide should be used with the How To Develop a Monitoring and Evaluation Plan.

To effectively integrate a theory of change into an M&E plan, SBC programs should:

- Use a theory of change process at the design stage and identify the important behavioral determinants that can be addressed with SBC programs.

- When selecting indicators for SBC M&E plans, consider measures that assess exposure to the program and determinants of behavior.

- Introduce qualitative studies such as in-depth interviews or focus group discussions throughout implementation to complement routine monitoring and help explain how the program is working.

- Share evidence on what works and how interventions can be improved to advance the FP and SBC fields and achieve greater programmatic impact.

Glossary and Concepts

SBC is a systematic, evidence-driven approach to improve and sustain changes in behaviors, norms, and the enabling environment. SBC interventions aim to affect key behaviors and social norms by addressing their individual, social, and structural determinants (factors). SBC is grounded in several disciplines, including systems thinking, strategic communication, marketing, psychology, anthropology, and behavioral economics. The role of human behavior is fundamental to the success of all development programs; thus, SBC is central to achieving many of USAID’s program outcomes.

Behavioral determinants include three categories: cognitive, emotional, and social.

- Cognitive factors address an individual’s beliefs, values, and attitudes (such as risk perceptions) as well as how an individual perceives what others think should be done (subjective norms), what the individual thinks others are actually doing (social norms), and how the individual thinks about him/herself (self-image).

- Emotional factors include how an individual feels about the new behavior (positive or negative) as well as how confident a person feels that they can perform the behavior (self-efficacy).

- Social factors consist of interpersonal interactions (such as support or pressure from friends) that convince someone to behave in a certain way as well as the effect on an individual’s behavior from trying to persuade others to adopt the behavior as well (personal advocacy)

Source: Ideation an HC3 Research Primer

Factors affecting health behaviors:

- Demand factors are the political, socioeconomic, cultural, and individual factors, such as geographic and financial barriers, that influence demand.

- Supply environment factors includes things such as personnel, facilities and space, equipment, and supplies. They also include planning and implementation of the main program functions: management; training; distribution of supplies; information, education, and communication efforts; and research and evaluation.

Process indicators track how the implementation of the program is progressing. They help to answer the question “Are activities being implemented as planned?”

Outcome indicators track how successful program activities have been at achieving program goals. They help to answer the question “Have program activities made a difference?”

Source: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/ms-96-03/at_download/document

Resources and References

Resources

Monitoring and evaluation resources

- Measure Demographic and Health Survey and UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys

- PMA 2020

- USAID Performance Indicator Reference Sheet (PIRS) Guidance & Template

- Croft, Trevor N., et al. 2018. Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF.

- The Family Planning and Reproductive Health Indicators Database. Measure Evaluation

SBC monitoring and evaluation resources

- (SBC) indicator bank for family planning (FP) and service delivery

- The Compass’s SBC How-to guides: How to develop Indicators

- Breakthrough RESEARCH’s Twelve recommended indicators for Family Planning Social and Behavior Change Programs

- Breakthrough RESEARCH’s Strengthening Social and Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation in Francophone West Africa

- Breakthrough RESEARCH’s Guidelines for Costing Social and Behavior Change Programs

- IRH’s Learning collaborative to advance normative change

- UNICEF Behavioral Drivers Model (BDM)

- UNICEF BDM Conceptual Framework

References

1Ajzen, I. 1991. “The theory of planned behavior,” Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2): 179–211.

2McLeroy, K. R., D. Bibeau, A. Steckler, & K. Glanz. 1988. “An ecological perspective on health promotion programs,” Health Education & Behavior 15(4): 351–377.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank Laura Reichenbach and Amanda Kalamar of the Population Council for their technical guidance and review; Sherry Hutchinson of the Population Council for design support; Chris Wharton (consultant) for editing; and Kristina Granger, Joan Kraft, Angie Brasington, and Lindsay Swisher of USAID, who provided valuable feedback during the development of this brief.

Suggested Citation

Breakthrough RESEARCH. 2022. “How to use a theory of change to monitor and evaluate social and behavior change programs,” Breakthrough RESEARCH How-to Guide. Washington, DC: Population Council.

Cover photo credit: ©Dominic Chavez/The Global Financing Facility (Cropped, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). This photo was taken prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

©2022 The Population Council. All rights reserved.