Introduction

What is Interpersonal Communication?

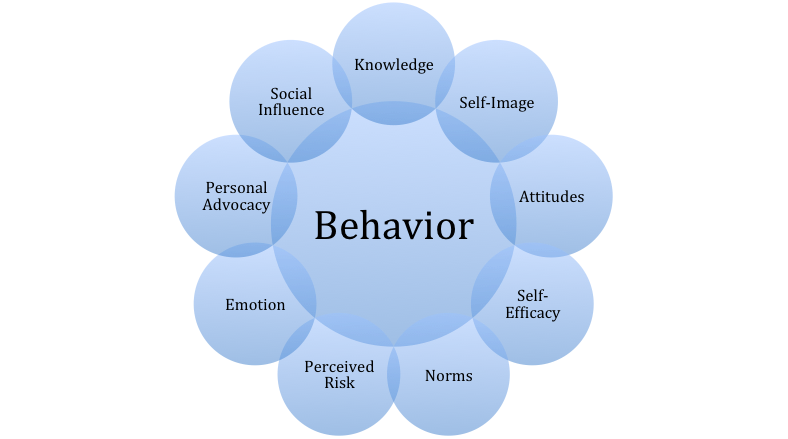

Interpersonal communication (IPC) is the tailored exchange or sharing of information, thoughts, ideas and feelings between two or more people to address behavioral determinants of health. It is influenced by attitudes, values, social norms and the individuals’ immediate environment. IPC can be one way or two way. It can also be verbal, non-verbal or both. Types of IPC include one-on-one interactions (at clinic or community), small group interactions, large group discussions, hotlines, supportive supervision visits, peer education, parent-child or inter-spousal communication.

People often engage and communicate better when they have shared values and attitudes or can at least see things from each other’s perspective and accept each other’s values and attitudes.

| Definition | Influenced By |

|---|---|

| Values (individual and community) are social principles, goals and standards | Family, religion, friends, education, experience and cultural factors |

| Attitude is a state of mind or a feeling; a mental position in relation to an issue | Values |

Interpersonal communication builds on values and attitudes for interaction and information sharing, skills and persuasive arguments with one another for better health behavior.

Why should IPC be used?

IPC is a channel that allows for exploration of attitudes and values and determinants of behavior of the participants. IPC reaches participants with tailored information that promotes specific healthy behaviors in an environment that allows for skills building/practice and exchange of information with peers. There is immediate feedback between those involved.

This direct, human contact and the ease with which information can be immediately clarified can help overcome certain challenging barriers to behavior change that general information through community, mass media or other media cannot easily address. If this is what the communication program needs, then IPC should be used. This choice is discussed in detail in Step One of this guide.

Who can use interpersonal communication?

In the context of social and behavior change communication (SBCC), interpersonal communication is most useful for peer educators, IPC agents or communication agents, community health workers, community-based distributors, counselors in a clinical or community setting, help line or hotlines, during community discussions, inter-spousal, parent-child or student-child communication and also when doing personal advocacy with influential people on a health issue.

Who should develop IPC interventions?

A small, focused team of key communication and creative staff should lead the development process of IPC tools. It may be helpful to include counseling and content experts who can guide the sections on counseling skills and technical content respectively.

When should IPC interventions be developed?

Once the situation analysis, program analysis and audience analysis are complete and SBCC messages are designed, it is time to select the appropriate channels of communication to fit the audience’s needs. While learning how to develop a channel mix, IPC is one of the channels to consider.

Learning Objectives

After completing this interpersonal communication guide, the team will be able to:

- Identify when IPC would be an appropriate channel to use

- Identify the type of IPC tool or intervention that would be most appropriate for an audience

- Assess if existing counseling/facilitation skills are adequate and improve any gaps or shortcomings through skills building

- Determine whether any existing IPC materials can be used, either in their current or an adapted form, or whether new materials need to be developed

Estimated Time Needed

Developing IPC interventions can take anywhere from a few weeks to a few months depending on the nature and complexity of the activity.

Prerequisites

Steps

Step 1: Decide Whether IPC Is a Suitable Intervention for the Priority Audience

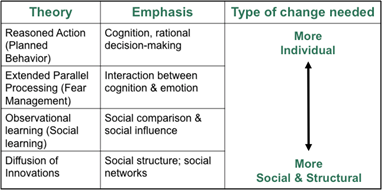

The decision to use IPC depends on two variables: the characteristics of the audience and the characteristics of the type of intervention needed to address behavioral determinants of health. Refer to the audience analysis to determine: what media the priority audience is exposed to, their key influencers, and their preferred sources of health information and opinion.

Refer to the audience analysis that was conducted to determine their information needs. Do the participants need facts, persuasion, motivation, support etc. in order to adopt the recommended behavior? Knowing what was identified in the audience analysis will help determine the type of information intervention that is needed.

IPC is a resource intensive intervention and therefore should be used when one or more of these hold true:

- The audience is not reached by other channels or does not regularly access health services

- Information needs to be reinforced, clarified and discussed in depth – social norms or cultural barriers that need to change

- Content is challenging or sensitive

- Demonstrations are required like mixing ORS, putting on a condom correctly, hand washing correctly, etc.

- When social support is a key determinant of the behavior being addressed. The perceived lack of social support could be addressed by creating and engaging in discussion. For example, people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA), breastfeeding mothers, or youth.

Fill out the following table to determine if IPC is a good fit.

| Audience | Preferred Information Sources (check all that apply) | Information Needs (Check all that apply) |

|---|---|---|

| [Sex, age range, geographic, psychographic, socio-economic, other] | Friends/peersFamilyLocal community, traditional and religious leadersCommunity health workerFacility-based providerTelevisionRadioPrintSocial mediaMobile phoneInternet | Perceived lack of social support to start or maintain behaviorIn-depth information on a difficult conceptConfidential or private discussion of a sensitive conceptDiscussion of myths and misperceptionsDiscussion of a health behavior between two involved partiesDemonstration of method use |

If the priority audience’s preferred information source includes at least one of the first four listed in the table above AND it includes at least one of the information needs listed in the third column, then IPC may be a suitable intervention.

Step 2: Decide Which IPC Method to Use and Identify Supportive Tools Needed

If IPC is identified as a potentially effective intervention to reach the priority audience, consider the IPC method that will work best for the program. There are three aspects to the IPC approach:

a. The human component (interpersonal skills of the IPC agent)

b. The tools (supporting materials to guide the counselor/ facilitator in method and content)

c. The location or setting where the IPC takes place

Use the table below to determine which IPC methods and tools the program will use, based on the audience’s information needs.

| Audience Information Needs | IPC Method | Tools to Support IPC | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-depth information on a difficult conceptConfidential or private discussion of a sensitive conceptDiscussion of myths or misperceptions | One-on-one counseling session between client and clinic health worker, community health worker, counselor (in person or through hotline/helpline), peer educator, communication or IPC agent | Counseling guideInformational flip chartVideosWall postersPeer education guide | Family planning counseling kit and flip chartCounseling guide for HIV hotlineYouth peer education manual |

| Discussion of a health behavior between two involved parties | Inter-spousal, parent-child, or teacher-student discussion | Discussion guide with tips for navigating the conversation | ART disclosure guide (parent-child)Discussion guide for newly married couples |

| Addressing perceived lack of social support to start or maintain health behavior | Facilitated support group discussions | Discussion guide | PLWHA support group discussion guide |

| Demonstration of method use and modeling how to discuss and negotiate | Demonstration of skills | Video or print teaching aidMaterials for demonstrationRole play to demonstrate discussion and negotiation | How to put on a condom correctlyHow to mix ORSHow to wash hands correctly |

Using the above table as a guide, fill out each column of the Tools Template (see Template 1: IPC Methods and Tools).

Determining the IPC method suitable for the audience is the first step. The next step is to look at whether the IPC agents have the requisite skills and tools they need to effectively execute the IPC method.

Step 3: Assess and Build Counseling and Facilitation Skills

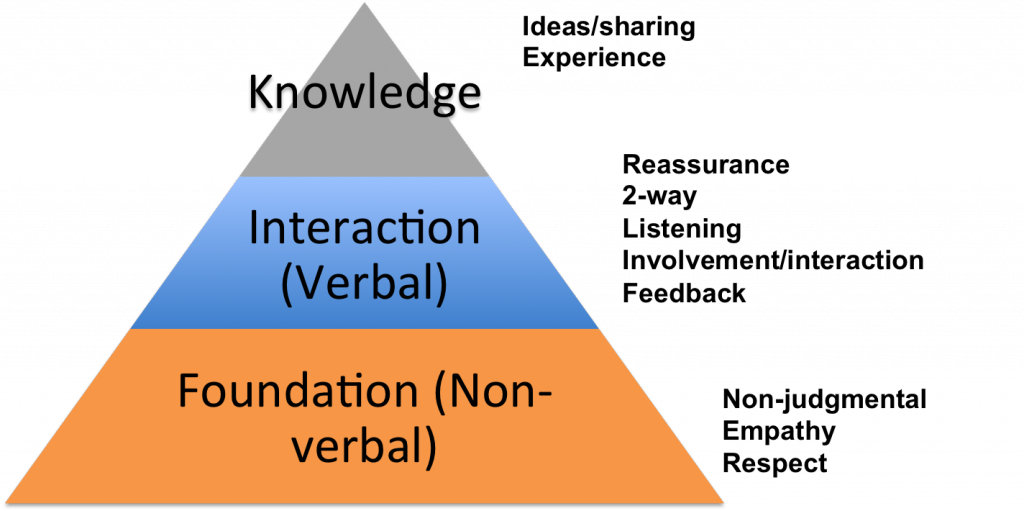

Interpersonal counseling on health issues and related health behaviors requires a specific set of skills designed to facilitate informed decision-making.

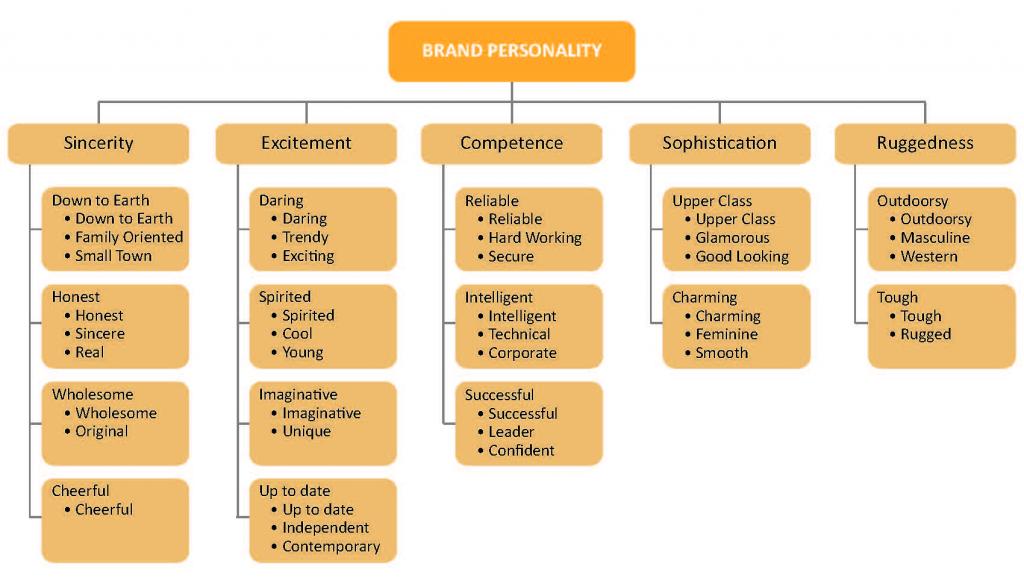

Also, IPC agents, whether they are providers, peer educators, helpline counselors or any other kind, bring their own personalities, values, judgment and interpersonal skills to the IPC approach.

There are many ways to assess IPC agents’ communication skills. One example of a communication skills assessment can be found here. For more in-depth assessment tools, see the Resources section.

Although many counselors may have had basic training in counseling and facilitation skills, If the program has identified a gap or weakness in this area, then there is a need to strengthen and build those skills to ensure effective IPC.

Some of the key aspects of good counseling include:

- Non-judgmental openness to what is being discussed. Putting aside one’s own value judgments and being open to see the issue from the audience’s point of view

- Listening actively to what the client/ individual/ group has to say

- Summarizing what has been heard

- Paraphrasing what has been heard to confirm it has been understood correctly

- Reflecting on what has been said and what can be done as positive action going forward

- Praise, encouragement and reassurance to help clients practice or continue to practice the positive health behavior

- Referral services and products that the client will require to practice the health behavior

Management/oversight in the form of supportive supervision will help better equip users to design programs, appropriately train and supervise staff, and manage and adapt their IPC programs.

Step 4: Assess and Plan Development of Effective IPC Tools

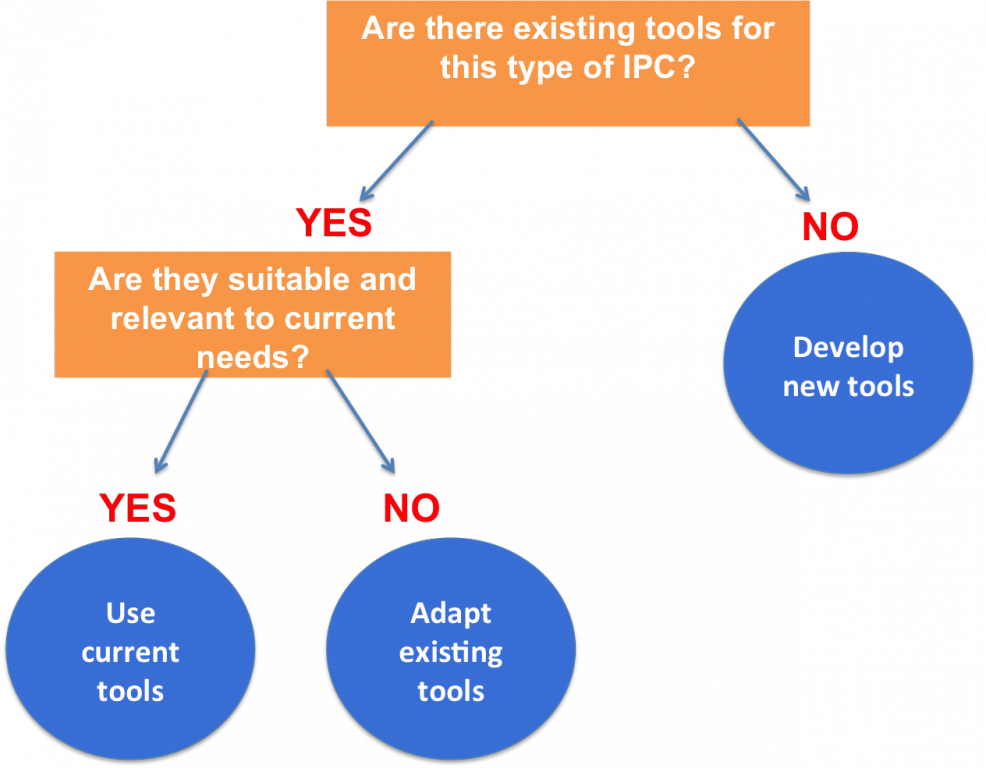

Counselors and facilitators need the help of good quality IPC tools to be most effective. These tools may be adapted or created from scratch to suit the purpose and context in which they will be used (see the Materials Adaptation Guide and the Materials Development Guide for more detailed guidance on materials). Answer the following questions to help determine a course of action:

Effective IPC tools should include the following elements:

- A clear focus on the identified primary audience

- Well-articulated objectives of what will be achieved by using this tool

- A reminder of basic communication and facilitation skills

- Scripts, facilitation guide and talking points where helpful and relevant

- Correct and consistent information about the health issue/ behaviors being discussed that are consistent with program and national strategy

- Glossary of key words, health/ technical terms and phrases with translation into the local language for ease of reference for counselor and facilitator

- List of frequently asked questions about the topic and their answers

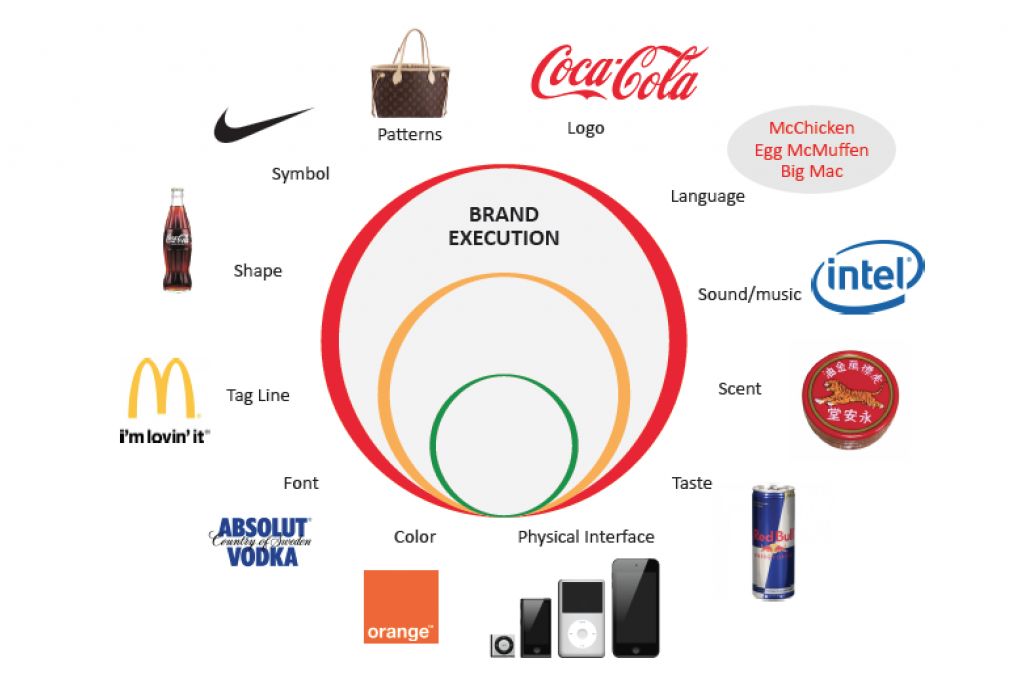

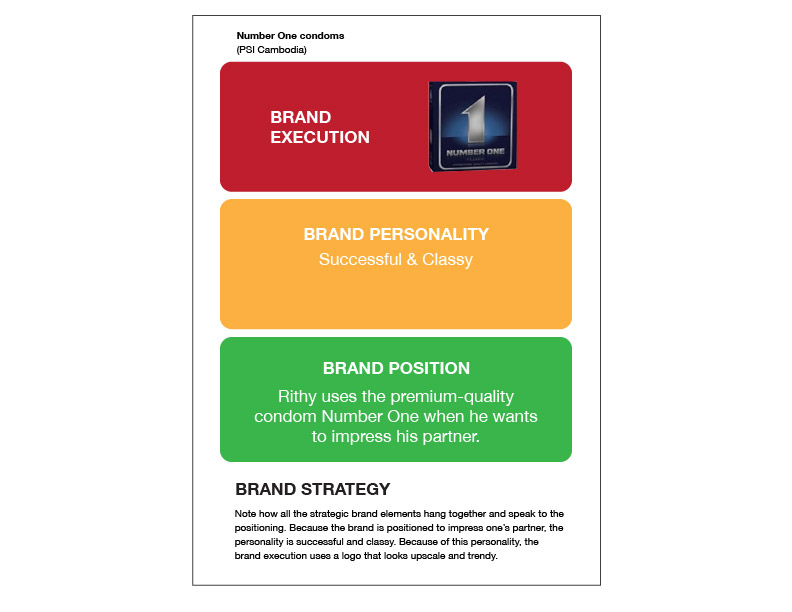

- Links to other elements of the program through visual and audio clues (taglines, logos, call to action etc.)

- List of additional resources for further reference on the topic

Some IPC tools are also accompanied by teaching aids like:

- Short, informational videos

- Posters or flip charts with attractive visuals and simple information to help with explanations

- Take-home materials to reinforce key information

- Models or props to help with demonstrations

Step 5: Develop IPC Intervention

After completing the above steps, the team will be clear on the following:

- Whether IPC is an appropriate intervention for the campaign

- The IPC method best suited to the audience and the supporting tools that will be needed

- The skill level of the counselors and steps to strengthen those skills if necessary

- The availability of existing tools or whether development of new tools is necessary

With this information in hand, the team is now ready to develop the IPC intervention. See the Resources section for resources that guide the development of quality IPC interventions.

Templates

IPC Methods and Tools Template

Tips & Recommendations

- IPC is effective when done well. Careful design and training of the facilitators or counselors in IPC techniques will significantly improve the effectiveness of the IPC session

- IPC works well when also combined with other channels like print (for take-away information and posters that reinforce messages)

- There are many tried and tested IPC tools available – see if any can be adapted to the current needs before developing new materials.

- Counselor training is a critical element of IPC to ensure that the skills of the counselor increase the effectiveness of the IPC interaction.

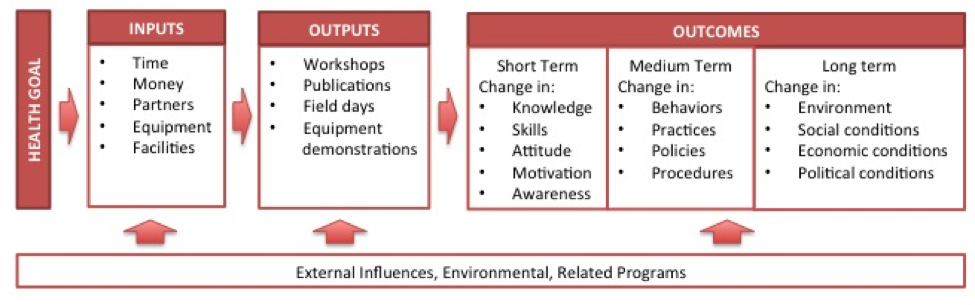

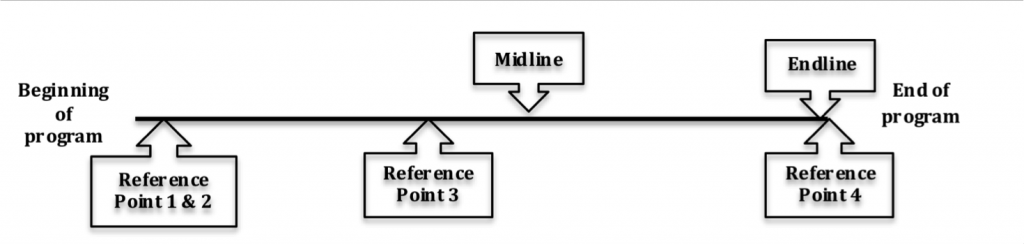

- Supportive supervision and oversight of IPC agents is a critical component of success in IPC programs. Additionally, routine monitoring/evaluation of IPC activities/programs is important for program managers to inform supportive supervision, program adaptation, refresher training and tweaking tools used by IPC agents.

Lessons Learned

- IPC is an intervention heavily dependent on the quality of the IPC agent, tools and teaching aids and the location/ context where the IPC intervention takes place. It is critical to ensure that the counselor possesses the requisite skills and attitudes as well as has access to high-quality materials with the information and messages specific to what the project wants to communicate.

Resources and References

Resources

A Field Guide to Designing a Health Communication Strategy

Improving Interpersonal Communication Between Health Care Providers and Clients

When to Use IPC and When Not to

Counseling for Effective Use of Family Planning [Curriculum]

Social and Behavior Change Communication for Frontline Health Workers

The Balanced Counseling Strategy Plus [Toolkit]

References

• What Is Interpersonal Communication – Definition and 3 Myths by Lei Han – https://bemycareercoach.com/soft-skills/communication-skills/interpersonal-communication-definition.html

• ‘Green Book’ for Leadership in Strategic Health Communication – A workshop Manual (2015 Edition) Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs (CCP)