Introduction

__________________________________________________________

Click here to access this Guide in Arabic – مراجعة هذا الدليل باللغة العربية، انقر هنا

Click here to access this Guide in Portuguese – Guias em Português

__________________________________________________________

A creative brief is a short, written document used by project managers and creative professionals to guide the development of creative materials (e.g. drama, film, visual design, narrative copy, advertising, websites, slogans) to be used in communication campaigns. Usually, it is no more than two pages in length, sets the direction, defines the audience(s), focuses on the key messages and shows the desired results for an SBCC campaign or materials.

The creative brief is part of the design phase in the communication process. The creative brief should be based on a communication strategy to ensure creative deliverables align with the overarching strategic approach.

Why Develop a Creative Brief?

A creative brief is the guidepost for creative deliverables: it guides in-house experts, an advertising agency or a creative consultant in the development of messages and materials that fit within the campaign’s overall strategic approach.

A creative brief outlines the most important elements of the SBCC campaign (see Creative Brief Template):

- The key health or social issue to be addressed.

- The priority and influencing audiences (who the campaign will reach).

- The importance of reaching those audiences.

- The key behaviors to promote.

- The reason the audience(s) should adopt a specific behavior.

- The benefits of taking that action.

Who Should Develop a Creative Brief?

A small, focused team should develop the creative brief. Members should include communication staff, health/social service staff and, if available, research staff.

When Should a Creative Brief be Developed?

A creative brief should be developed by the team after conducting a situation analysis and audience analysis. Data collected during these analyses inform the creative development process. The creative brief will guide the process of message and materials development.

Estimated Time Needed

Completing the creative brief can take up to two to three days to develop depending on how complete the communication strategy is and whether the team needs to gather additional information.

Learning Objectives

After completing the activities in the creative brief guide, the team will:

- Understand the importance of a creative brief in designing communication interventions.

- Develop a creative brief that clearly identifies the purpose of the campaign.

Prerequisites

Steps

Step 1: Define the Purpose

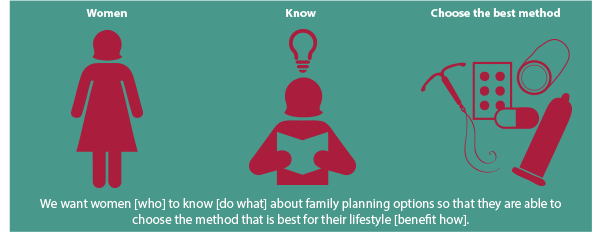

Prior to developing a creative brief, it is important to have a clear understanding of why messages and communication materials are being created for the health or social issue and audience. Define the purpose of the creative brief by completing the following sentence:

We want [this audience – who?] to [do what?] in order to [benefit how?].

The more specifically tailored the creative materials are to the purpose, the more likely it is that the SBCC efforts will succeed.

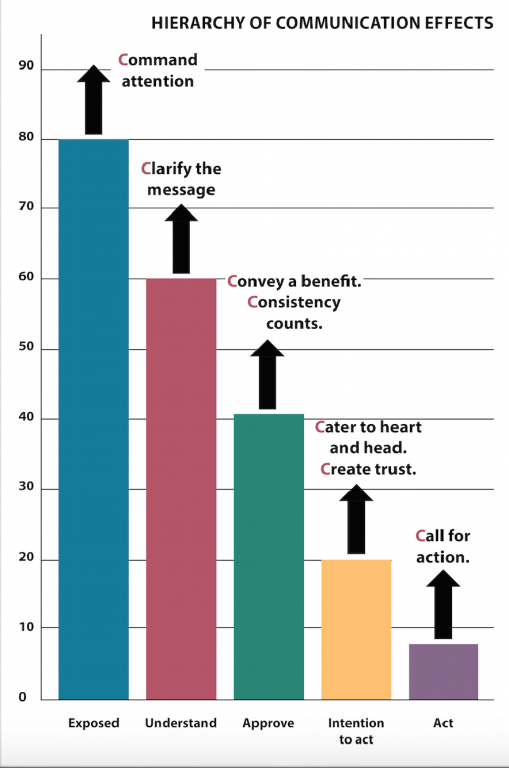

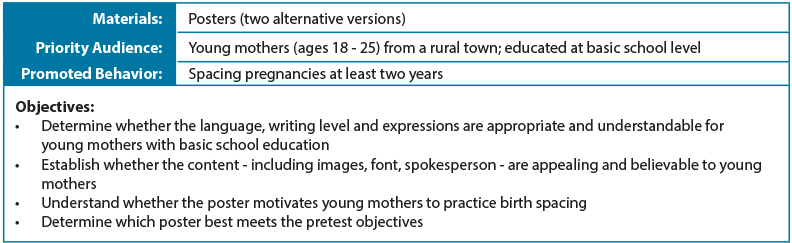

Step 2: Determine the Objectives

Creative brief objectives should be clear and specific. One way to write a good objective is to specify what the audience should think, feel or do as a result of exposure to the creative materials:

- What should the audience believe, think or know?

- What should it feel about the proposed behaviors/solutions?

- What should it do to immediately improve its (or its family’s) situation and well-being relative to the issue?

Step 3: Describe the Audience

To develop successful creative materials, it is critical to understand who those materials will address. This section of the creative brief should answer the following questions:

- Who is the audience for the creative materials?

- What does the audience care about?

- What does the audience currently think, feel and do in relation to the objectives set in Step 2?

Refer to the audience profiles developed during the audience analysis to produce a description that will help the creative team understand who the audience is. Include both demographic and psychographic characteristics.

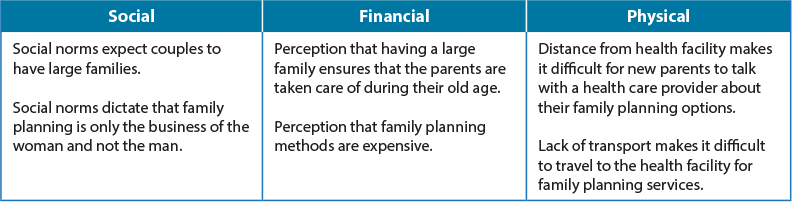

Step 4: List Competing Current Behaviors or Conditions

Make a list of current behaviors and conditions that prevent the audience from adopting the behavior(s) the communication materials will promote. These competing behaviors or conditions will be similar to those that were defined as social, economic and physical challenges or obstacles found in the situation analysis.

By creating this list, the creative team will be able to develop its messages more carefully and accurately by specifically addressing the barriers to adopting the new behavior(s).

Step 5: Highlight the Key Issue

Identify the most important issue that needs to be addressed. Think about one improvement (e.g. improving knowledge, increasing self-esteem or addressing myths about an illness or disease) and its potential effect on members of the priority audience. Even if multiple issues exist, each creative brief should focus on one audience, one message and one issue.

Step 6: Determine the Key Promise

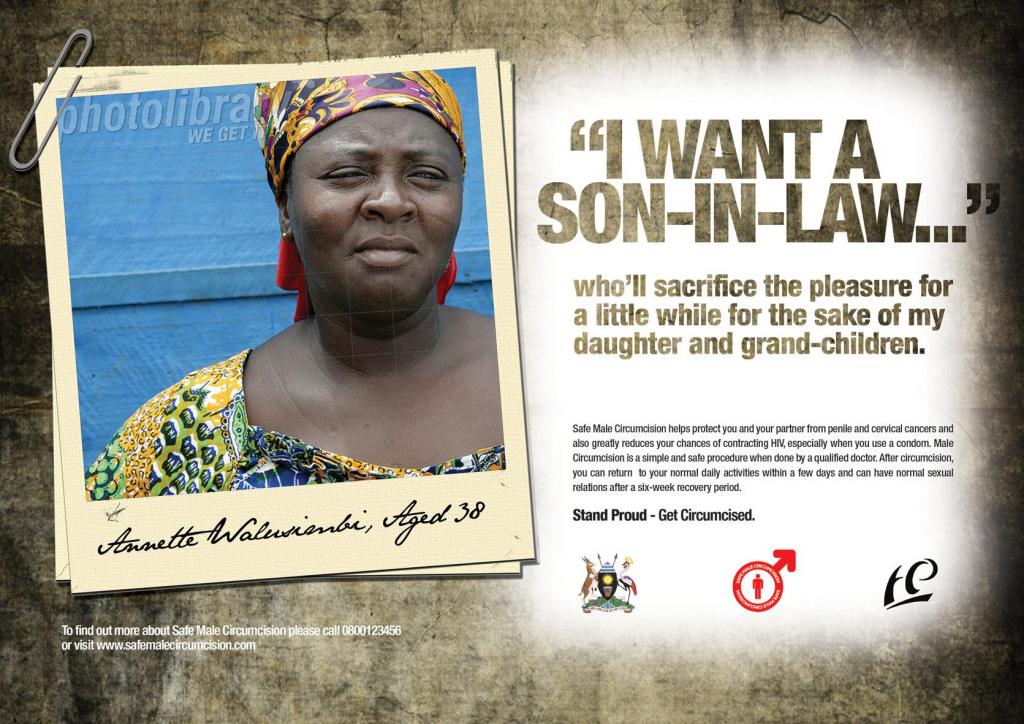

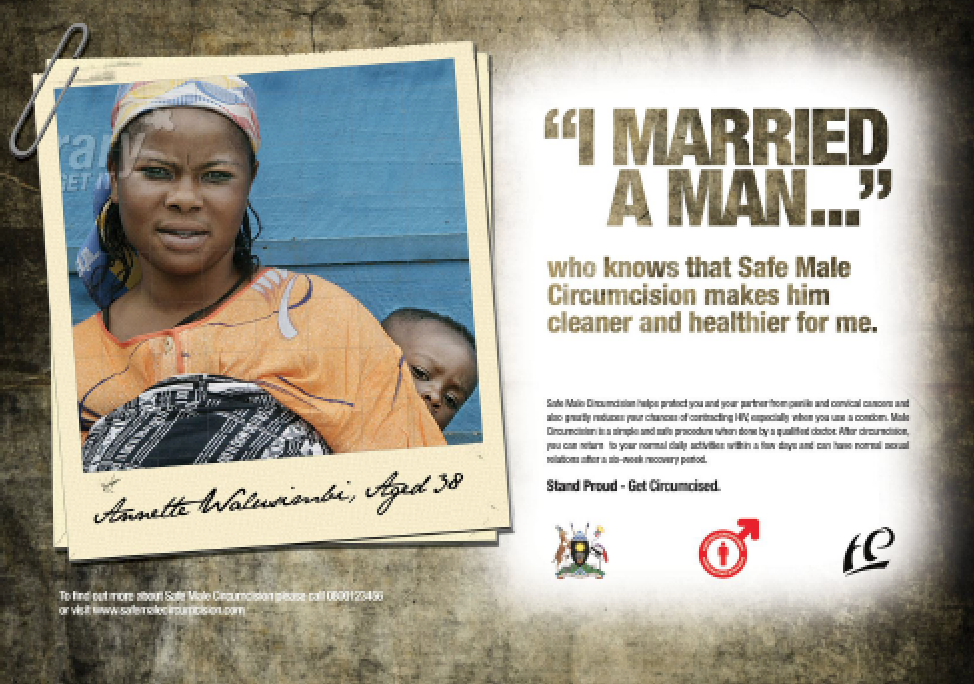

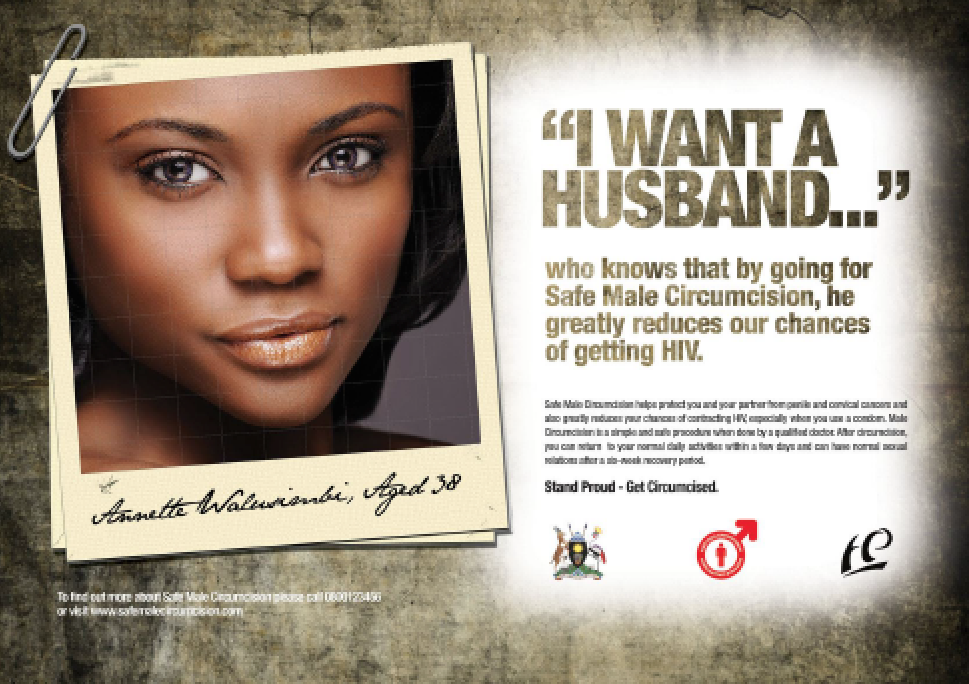

A promise expresses how the audience will benefit from using a product or taking an action. A promise to the priority audience must be true, accurate and of real benefit. The promise is not a product (e.g. surgical gloves). It is not an action (e.g. getting circumcised). It answers the question, “why should I do this?” Or “how will this help me?”

This promise hints at an action but highlights the benefit of that action.

Discuss among the creative team to develop a single promise for the campaign. It is best to write it as an “if…then…” statement. It may be useful to develop a few alternative ‘then’ options and pretest them among the priority audience to see which benefit resonates the most with them. Keep the consequences positive, since negative consequences can increase fear and disempower the priority audience.

Step 7: Identify Support Points

The audience needs believable, persuasive and truthful information to support the key promise. These can be in the form of facts, testimonials, celebrity or opinion leader endorsements, comparisons or guarantees. The kind of support points used will depend on what will appeal and be credible to the priority audience.

Step 8: Define the Call to Action

The call to action suggests a specific action the audience should take to receive the benefit of the promise. This action needs to be realistic and do-able. This helps the audience make a quick decision instead of delaying action or forgetting to take action.

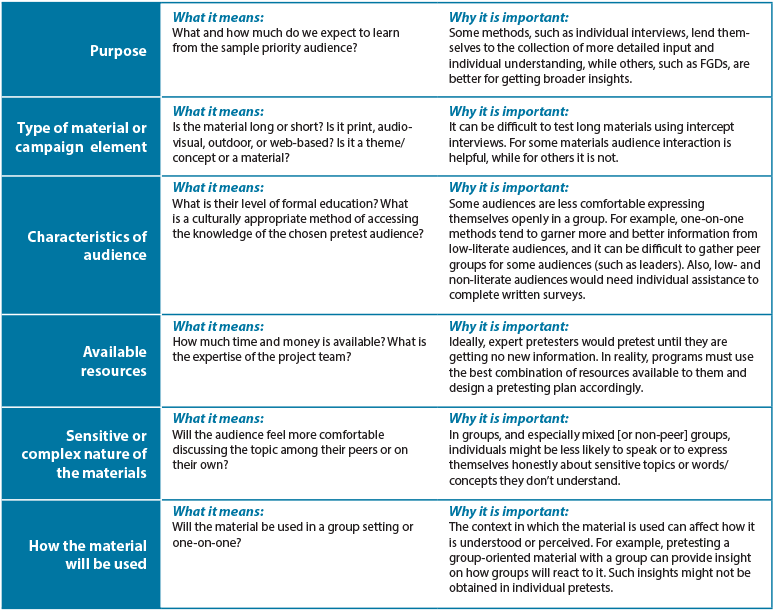

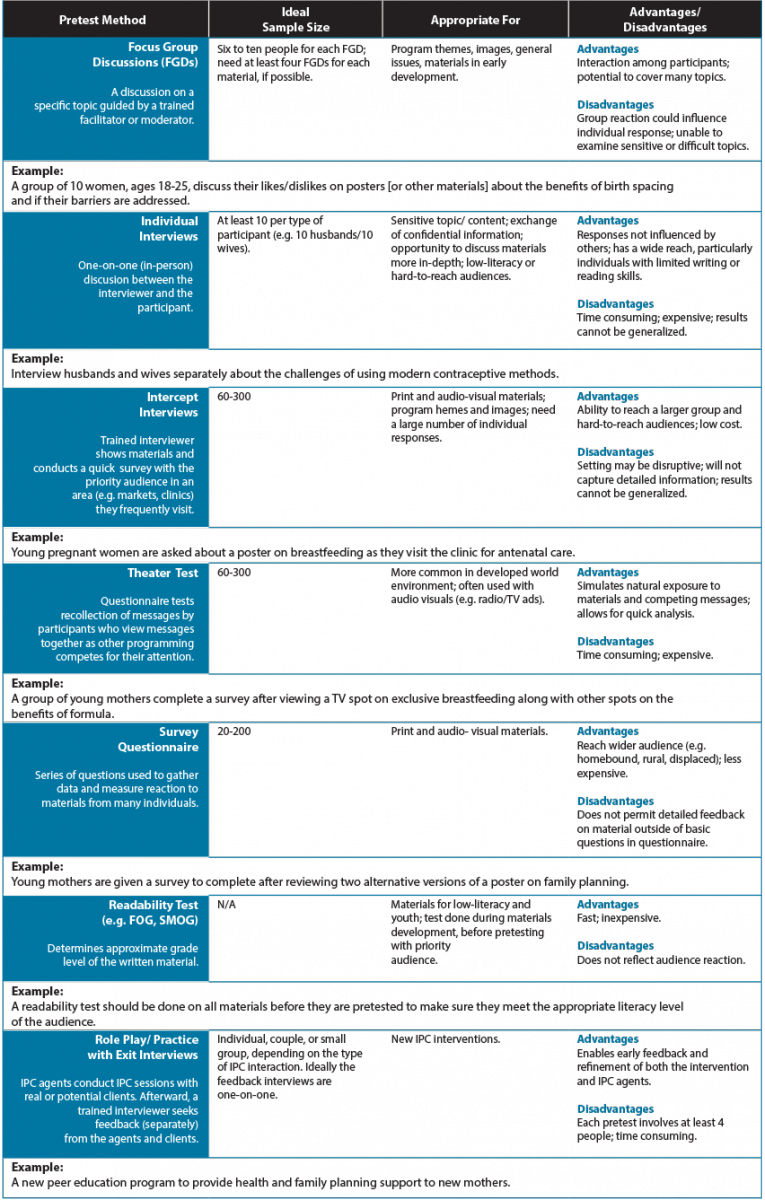

Step 9: Determine Creative Considerations

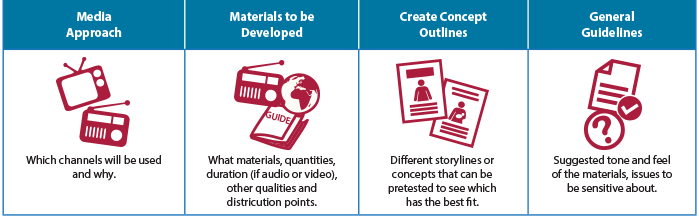

There are several factors that will impact the creative process and overall approach. Review the situation analysis and audience analysis to determine appropriate media and materials, as well as overall tone. Provide the creative team with information on the following creative considerations:

These creative considerations will guide the creative team in their development of messages and materials. Other considerations may include: geographic placement, language, any program requirements, literacy and branding and marking guidelines.

Step 10: Map the Timeline

The creative brief is the guiding plan for the internal team, agency or consultant hired to do the creative work. It should include a realistic timeline. The timeline should include each task (e.g. review, testing, revisions) with a realistic number of days for completion (see Timeline Template under templates). Keep the timeline in a place that is visible and will allow the team to stay on track. Be sure to update the team if tasks or the timeline changes.

Step 11: Develop the Budget

Anything that takes time and labor has a related cost. For example, someone from the team will likely have to travel to test materials. Be sure to identify all tasks and the cost (including pretests and revisions) of each task (see Budget Template under templates).

Templates

Creative Brief Budget Template

Creative Brief Timeline Template

Samples

NURHI Get it Together Creative Brief

Club Risky Business Creative Brief

Older Men and Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision (VMMC) Creative Brief

Tips & Recommendations

- Try to think of different and creative ways to get the message to the priority audience. For example, how would gossip spread in the community? Is it possible to use the same approach to spread a positive message?

Lessons Learned

- The creative brief helps to clarify the project’s goals and objectives.

- The creative brief provides a very good and concise historical record of the thinking behind the products produced for a campaign.

- Keep all creative briefs in one folder (electronic or print) for quick reference.

Glossary & Concepts

- A communication campaign includes a combination of approaches (usually including mass media in addition to community-based approaches) and provides multiple opportunities for exposure through a consistent theme that links program activities together.

- Demographic information is statistical data (e.g. age, sex, education level, income level, geographic location) relating to a population and specific sub-groups of that population.

- Priority audience is the group of people the communication campaign is aiming to reach.They may be the people who are directly affected by the health or social issue or who are most at risk of the issue, such as a new mother wanting to begin using a family planning method. Or they may be people who are best able to address the issue or who can make decisions on behalf of those affected, such as mothers and fathers of young children.

- Psychographics are the attributes that describe personality, attitudes, beliefs, values, emotions and opinions. Psychographic characteristics or factors relate to the psychology or behavior of the audience.

- Social norms are the rules or standards of behaviors shared by members of a social group.

Resources and References

Resources

The DELTA Companion: Marketing Made Easy

References

- The BLU Group – Advertising & Marketing. Seven Key Questions to Answers When Writing an Effective Creative Brief.

- Jeff Berry Rules. How to Write a Creative Brief.

- Raven. How to Write a Killer Creative Brief.

- Smart Insights. How to Write a Creative Brief that gets Results.

Banner Photo: © 2013 Valerie Caldas/ Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs, Courtesy of Photoshare