Introduction

Service providers play several roles within health systems. Their responsibilities may entail, but often are not limited to, client counseling and care, community mobilization and engagement, and managing supplies and logistics. A provider’s ability to perform these tasks effectively may be hindered by barriers within or beyond their immediate sphere of control or influence. A provider’s personal opinions and biases, attitudes and behaviors, capacity and skills, and working conditions may all impact their ability or motivation to deliver quality services.

Such facilitators and barriers are outcomes of a complex set of factors. Social and behavior change (SBC) interventions can help to identify and address some of the factors that lead to provider-side barriers to quality service delivery.

An SBC-based approach to addressing provider behaviors involves a strategic process of identifying individual provider perspectives on and needs for adopting desired behaviors and practices. This process starts with a provider behavior assessment, which is used to identify strengths, needs, gaps or best practices within a given service provider community. An SBC activity should be working toward a specific behavioral outcome for a population segment, thus the provider behavior assessment is conducted with a specific behavioral outcome in mind (e.g. youth contraceptive use, childhood immunization, exclusive breastfeeding, etc.).

Definition

A provider behavior assessment is conducted prior to initiating a provider behavior change intervention—and throughout a program intervention—to identify, understand, and prioritize the barriers service providers face in performing their job functions. Provider behavior is one entry point to addressing a behavioral outcome for a population segment, thus the assessment should be conducted in relation to a specific behavioral outcome or goal. The assessment results allow programs to strategically plan ways to most effectively motivate and support service providers to influence uptake of and deliver quality services to their clients. It primarily focuses on understanding facilitators and barriers that can be addressed through SBC approaches. There are various techniques that can support barrier analysis, including a doer/non-doer study or an examination of positive deviants. An assessment can be used with providers at any level of the health system, whether facility or community-based.

A barrier assessment typically seeks to answer questions such as:

- What are the incentives and obstacles providers experience in providing quality services?

- What are the values, norms and biases that influence provider actions?

- What are the provider behaviors that positively and negatively influence service quality?

- What are the techniques (words, actions, linkages) used by some providers to overcome difficulties in service provision and interact supportively with clients?

Why Conduct a Provider Behavior Assessment?

Providers have experiences, perspectives, and biases which may challenge or support their ability to adequately deliver quality services. It is important to have a better understanding of provider behaviors so they can be addressed or supported with evidence-based, targeted SBC solutions. SBC focuses on behaviors and not all provider barriers can be overcome through SBC interventions alone. SBC activities specifically seek to address providers’ knowledge and skills and their underlying motivations, norms, values, attitudes, and beliefs.

For example, In the context of routine immunization, service providers are among the most influential sources of information in community settings and serve as crucial facilitators in motivating demand for vaccination.* However, health systems challenges such as vaccine stockouts can cause frustration among caregivers and healthcare workers (HCW). SBC approaches such as strengthening the interpersonal communication skills of frontline immunizers can foster trust between HCWs and caregivers, increasing the likelihood that a caregiver will return for their child’s immunization appointment, even after experiencing a barrier such as a stockout.

A provider barrier assessment can help to:

- Identify the current and most important facilitators and barriers to delivering quality services in a facility or community settings.

- Identify provider needs, attitudes, motivations, and opportunities.

- Characterize provider perspectives that impact clients’ care-seeking behaviors.

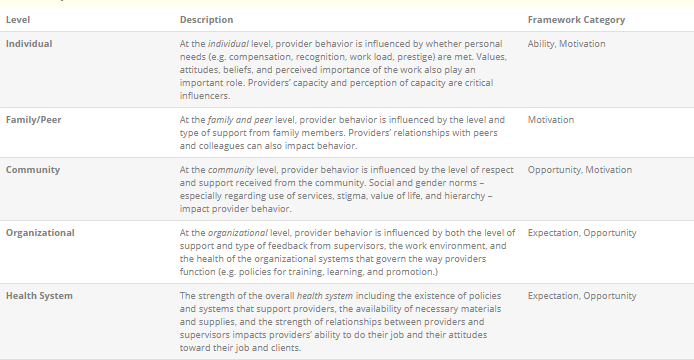

- Characterize individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and health system influences on provider performance.

- Identify areas needing capacity strengthening.

- Provide evidence to inform relevant SBC activities.

Who Should Conduct a Behavior Assessment?

A barrier assessment is best carried out by a team of individuals with an interest in improving the performance of service providers and the overall quality of health services. Ideally, the team will include a diverse group of stakeholders with sufficient access to providers, their supervisors, and community representatives. It is helpful to have the support of individuals with expertise in SBC, data collection and analysis, and service quality improvement.

Provider Behavior Assessment Process

- Conduct background research

- Define your audience

- Develop a data collection plan and instruments

- Analyze data and identify barriers

- Summarize and report findings

*Waisbord, S. & Larson, H. (June 2005). Why Invest in Communication for Immunization: Evidence and Lessons Learned. A joint publication of the Health Communication Partnership based at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (Baltimore) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (New York).

Banner image – © 2003 Center for Communication Programs, Courtesy of Photoshare

Learning Objectives

- Understand the relevance of conducting a provider barrier assessment

- Apply an approach to assess provider barriers and more effectively change provider behavior

Prerequisites

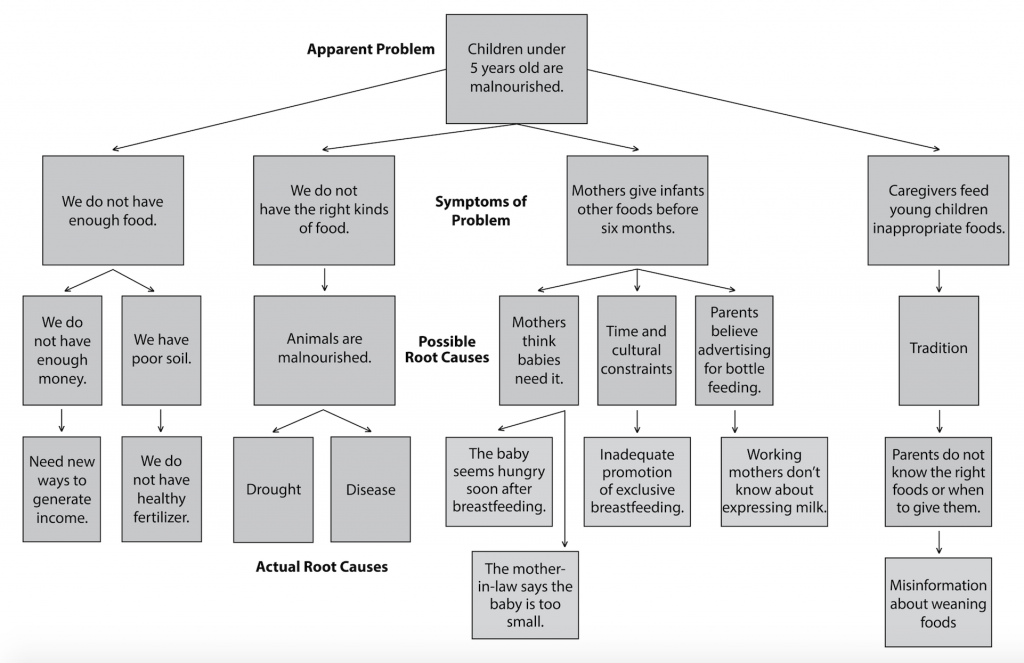

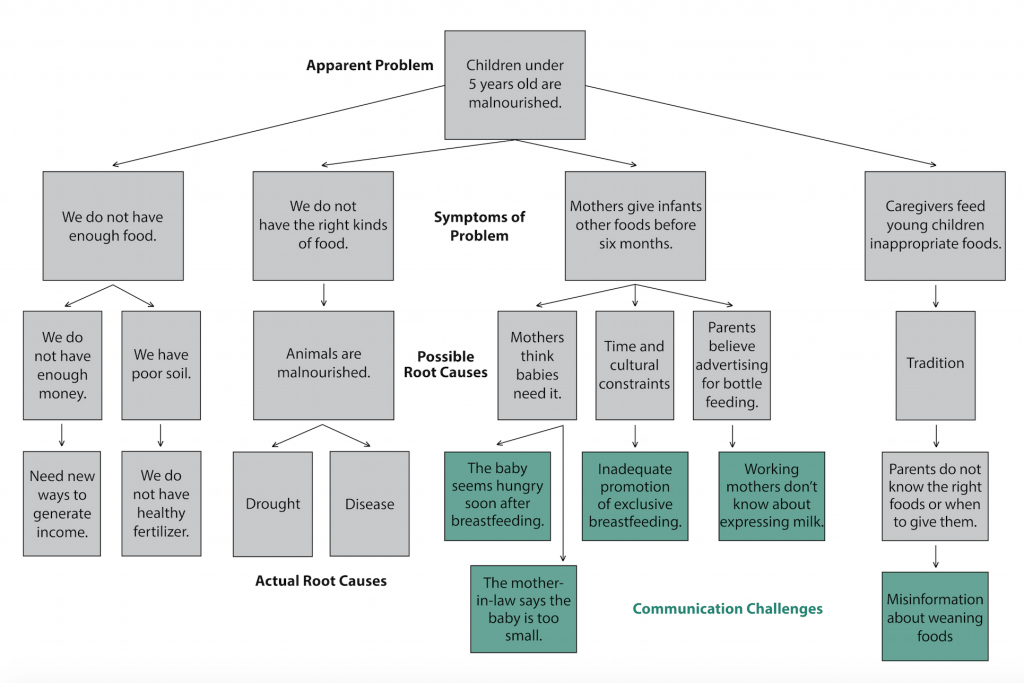

Carry Out a Situation Analysis and Root Cause Analysis

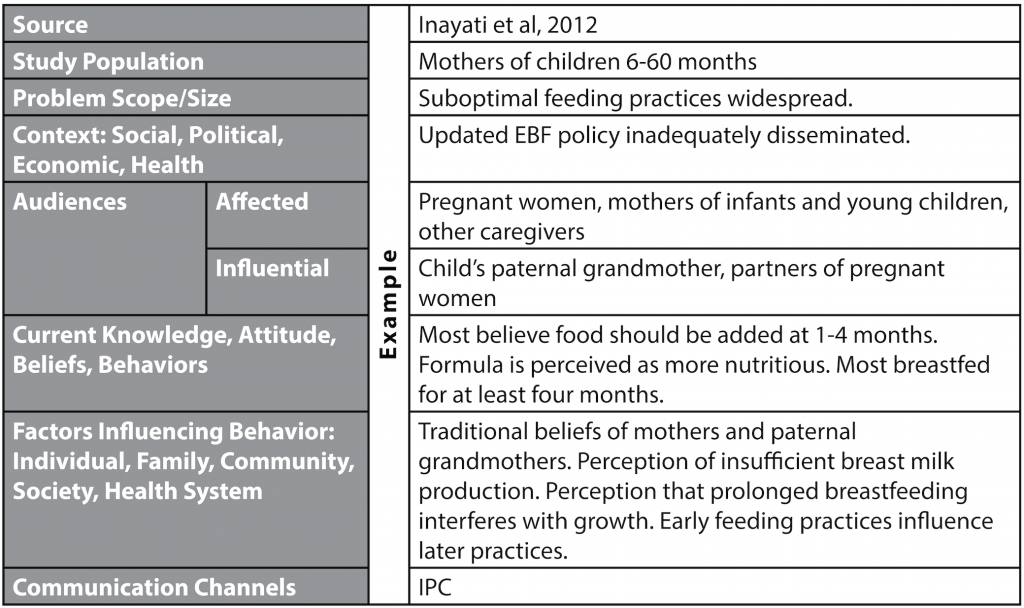

Before undertaking a provider behavior assessment, it is important to first have a clear sense of the context surrounding the specific behavioral outcome being impacted by provider behaviors. A situation analysis, which involves a systematic collection and study of health and demographic data, will help you identify the provider behaviors relevant to behavioral outcome you wish to address amongst your target audience. Reviewing evidence that provides insight into the social, economic, political, and health context in which the behavioral outcome exists will help establish whether service quality and provider-behaviors are issues constraining the behavioral outcome.

A root cause analysis will then help determine the extent to which provider behavior is a key constraint. The behavior assessment can then characterize the interactions between providers and clients and the factors that influence the nature of those interactions.

Steps

Step 1: Conduct Background Research

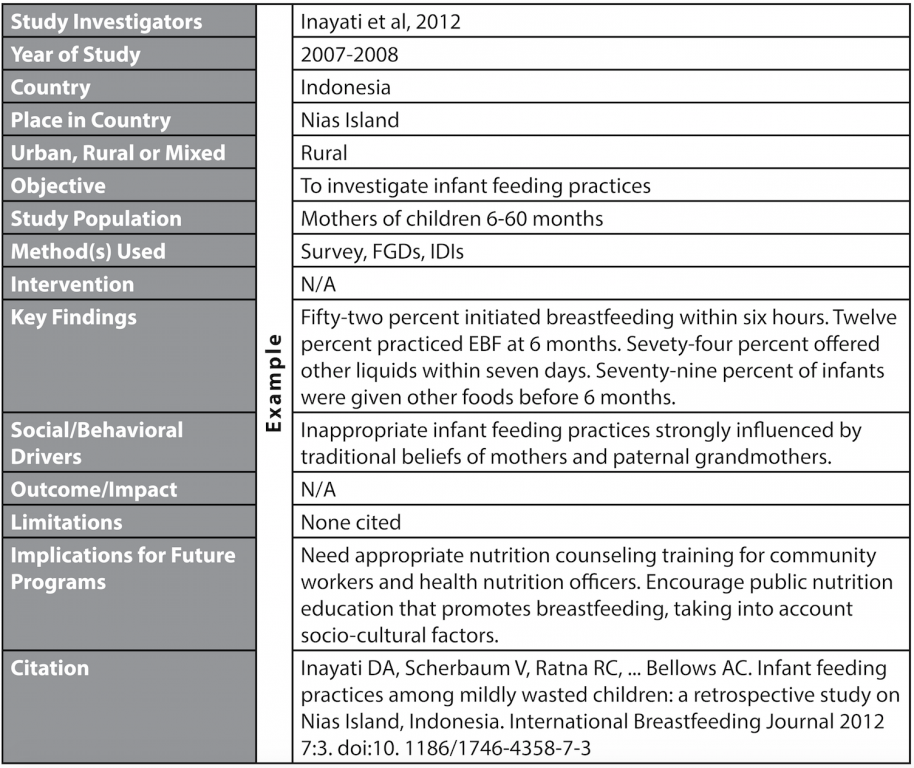

Use peer-reviewed and grey literature from public health and other relevant disciplines to identify gaps in knowledge about provider behaviors and perspectives. Start by investigating existing evidence on knowledge, attitudes, and practices through national or subnational data. If local data is not available or sufficient, review data from similar cultural, religious, or other contexts. The literature review should focus on defining the types of provider barriers and facilitators for service provision, and exploring the underlying cause of the barriers.

One such literature review was conducted by the by the Health Communication Capacity Collaborative in 2016. The review identified three key areas of factors impacting health care worker (HCW) behavior change: 1) knowledge and competency barriers in which HCWs lack the skills and knowledge to provide services; 2) structural and contextual barriers in which systemic and environmental factors affect HCW’s abilities to provide services; and 3) attitudinal barriers in which attitudes and societal beliefs influence HCW’s willingness to provide services. While literature reviews such as this one and the one you will conduct help to define types of provider barriers, they may not sufficiently identify the specific needs, attitudes, and behaviors of your provider community of interest. Further investigation is required to understand the characteristics and challenges of your provider audience.

To supplement the information gleaned from the literature review, consider interviewing key informants who can provide added perspectives on society, religion, and culture and how those factors might influence provider behavior. Key informant interviews are also a good opportunity to get a general sense of how service quality is defined; this will help you understand which provider behaviors and perspectives are impacting service quality.

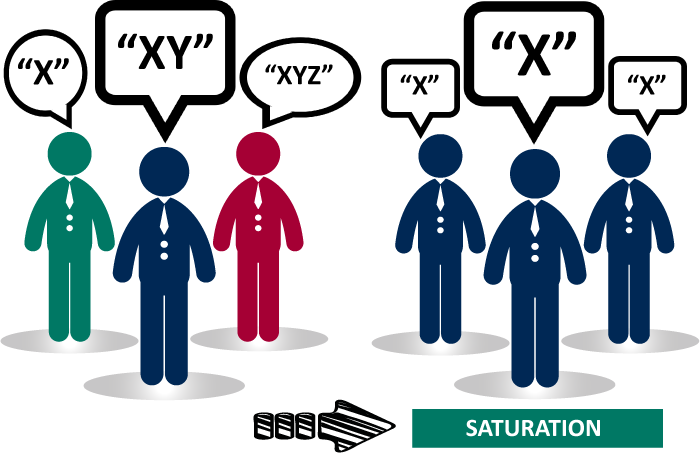

After conducting the literature review and key informant interviews, use the findings to classify provider archetypes into hypothetical audience segments to be further explored through qualitative research.

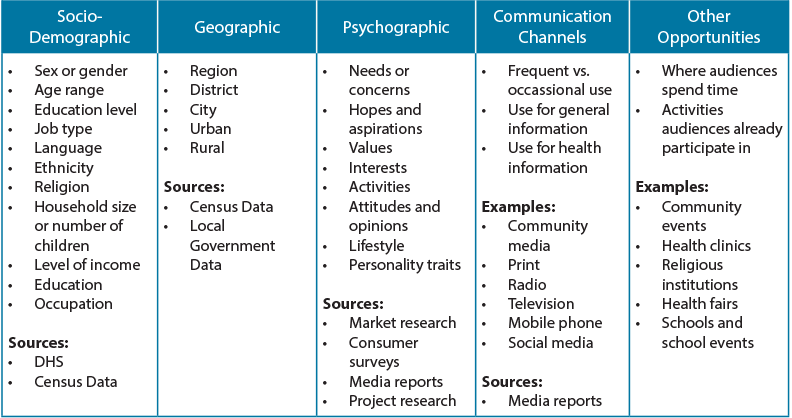

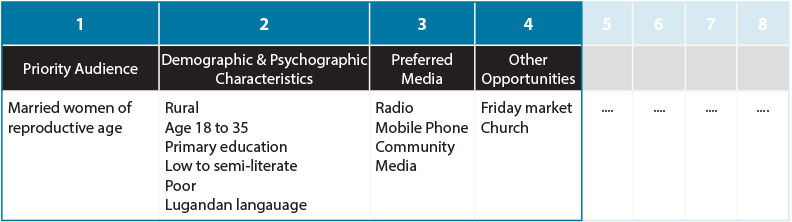

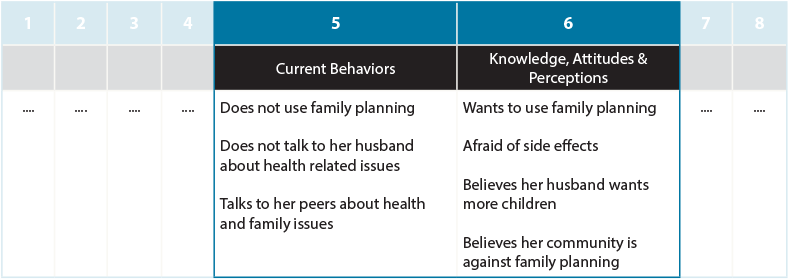

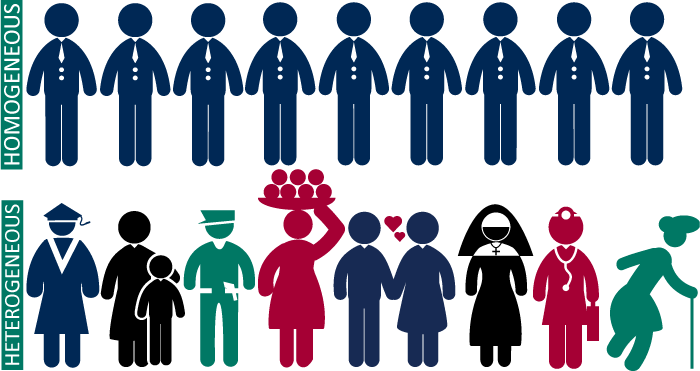

Step 2: Define Your Audience

When starting the assessment, it is important to think of providers as an audience in the same way you would define any other target audience for an SBC effort. The health system comprises various cadres of service providers with distinct and complementary roles. Tasks may be shared across facility-based providers such as physicians, midwives, and nurses; community-based providers such as health educators and community mobilizers; and community volunteers and outreach workers. As determined through the background research, the individuals working within those cadres have varying levels of education and experience as well as distinct needs, motivations, and challenges.

To define your hypothetical segments, consider the variables that may facilitate behavior change among your provider audience. The various and unique ways in which different types of providers are motivated and influenced will likely impact their interactions with different client segments. After you have defined a set of hypothetical segments, you may choose to focus on a specific segment of providers for further qualitative inquiry.

In treating providers as an audience segment, it is important to remember that, just like the clients they serve, providers are community members who operate within a social ecological system and are subject to multiple spheres of influence. Throughout the barrier assessment, return to the framework below to consider the ways in which individual, family, peer, community, organizational, and health system influences might affect what you are observing and learning about provider barriers.

Step 3: Develop Data Collection Plan and Instruments

The background research will give you an overview of the factors affecting provider performance, the nature of providers’ work in the area of interest, the expectations placed on service providers, and how provider performance is measured. The segmentation exercise will help you develop a segment model based on provider archetypes and the categories of barriers identified in the literature review.

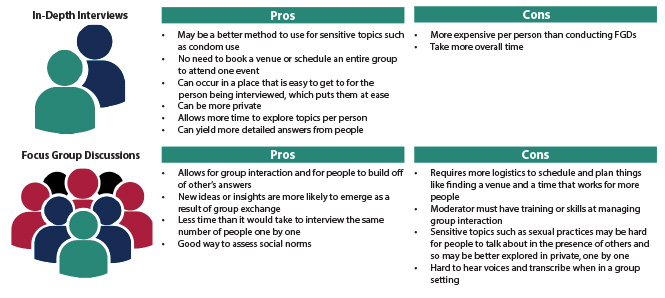

To plan a social and behavior change intervention, you still need to identify the major drivers of specific barriers encountered by your hypothetical provider segments. Developing a data collection plan, including data sources, and methods of collection will help you identify these major drivers. Depending on resources and needs, you may decide to use qualitative or quantitative research to identify the specific behavioral, social, and technical barriers that impede the behavior change objective. Identify the individuals or data sources that can provide information to answer your questions and how will you engage with them. Your qualitative or quantitative study sample should be as inclusive as is feasible to ensure provider barriers, client experiences, and service quality are articulated from multiple perspectives. Consider the size of each group of individuals from which you would like to gather data. Tools such as the sampling overview document can help you think through the issues associated with reaching each group that is providing data.

Consider exploring questions such as:

- What is the provider’s current behavior regarding the targeted service/health area?

- How do gender norms and roles factor into provider’s attitudes and practices?

- Does the provider perform the desired behavior all the time, sometimes, or not at all?

- What are the reasons the provider does not consistently practice the desired behavior? Do they lack adequate resources, time, or pay, or are the barriers tied to lack of knowledge, skills, or other ideational factors?

- What is the provider’s current attitude about their job, the service, or the clients with whom they work?

- Are they happy with their job? Do they have any biases toward the services they are being asked to provide or toward the clients they see?

- What does the provider perceive to be the benefits of adopting the targeted behavior?

- What is the provider most motivated by—peer support, social status, financial incentives?

Note: It is crucial to pretest your research instruments before fielding them.

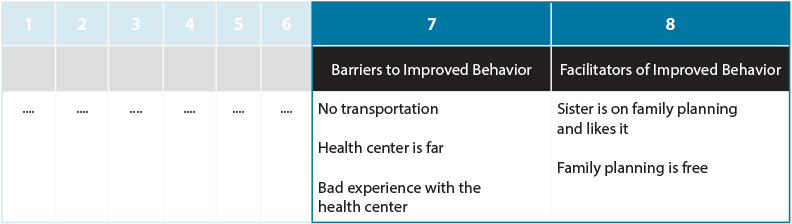

Step 4: Analyze Data and Identify Facilitators and Barriers

Conduct the appropriate type of analysis on each type of data you collect. For example, conduct qualitative thematic analysis on focus group data. The members of your team with experience in data analysis will be particularly useful here. Be sure to note any differences by segment and by gender. Summarize how the data responds to each of your questions. The result should be a set of biographical, situational, and societal drivers of provider job performance specific to your provider segments.

| CASE STUDYThe USAID-funded Transform/PHARE project conducted a barrier analysis and positive deviants study of family planning providers in Côte d’Ivoire. Some of the common provider barriers identified during this study include:● Personal opinions and biases○ Cultural or traditional biases■ Some providers tell married women they cannot have access to family planning methods or that they must have spousal approval first.○ Age or parity of client■ Some providers promote the idea that there are a minimum number of children a woman must have before she can have access to injectable contraceptives.■ Some providers will make judgments about young clients seeking family planning and mislead young women, particularly those who are unmarried, by telling them there are age restrictions for obtaining contraceptives.○ Negative perceptions of the service● Capacity and skills○ Lack of evidence-based, current knowledge and experience○ Lack of knowledge of certain methods■ Some providers may wrongly believe that injectables delay fertility, cause infertility, and are unsafe.● Attitudes and behaviors○ Attitudes toward the client■ Belief they know what the client needs before consulting with the client■ Enjoyment in working with the client population○ Personal bias against a particular intervention○ Ease of offering the serviceSome providers recommend family planning methods that are easier and faster for them to provide, rather than finding out what is most convenient for the client |

Step 5: Summarize and Report Findings

Now you can define the specific behaviors you want to change and decide which behaviors will be the focus of your intervention. Record these insights in a provider profile, which will help summarize the characteristics of the providers you intend to target and offer insights on how to position the desired behavior change.

Work with community or organization representatives to review the data collected and its analysis; identify needs; agree on prioritization of these needs; and plan interventions to address them. As with any other behavior change intervention, it is imperative the intervention, its messaging, and channel of delivery are appropriate to the audience segment to most effectively target your interventions. To conclude the assessment, stakeholders should agree on who will address each barrier and how behavior change will be monitored.

Tips & Recommendations

- When conducting qualitative research, consider analyzing documents such as performance reviews, quarterly reports, survey results or reports, community assessments, and employee satisfaction surveys that may also help answer your questions.

- Conducting focus group discussions, in-depth interviews, and/or participatory methods of inquiry with community members and key health system stakeholders can provide broader insight.

- Barriers and needs that cannot be addressed solely through SBC interventions are likely to surface. Engage decision makers in the assessment and analysis to motivate action to be taken on all identified needs.

- Involve community stakeholders throughout the assessment process to motivate the community to come together to help address provider barriers.

- Each factor impacting the performance of service providers should be examined through a gender lens to help develop a more comprehensive analysis, needs identification, and responsive intervention planning.

- Additional guidance and support on designing behavior change interventions for providers can be found in the Designing a Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBCC) Intervention for CHW Behavior Change and the Designing an SBCC Intervention for FBP Behavior Change I-Kits.

Resources and References

Resources

Barrières des prestataires et déviants positifs/ Provider barriers and positive deviants

Beyond Bias: Provider Survey and Segmentation Findings

Provider Behavior Change Implementation Kit

Provider Behavior Change Toolkit

Service Communication Implementation Kit

Barrier Analysis Facilitator’s Guide

Strategies for Changing the Behavior of Private Providers

References

Beaulieu, M.D., Haggerty, J.L., Beaulieu, C., Bouharaoui, F., Lévesque, J.F., Pineault, R., … Santor, D.A. (2011). Interpersonal Communication from the Patient Perspective: Comparison of Primary Healthcare Evaluation Instruments. Healthcare Policy, 7(Spec Issue), 108–123.

Davis Jr., & Thomas P. (2004). Barrier Analysis Facilitator’s Guide: A Tool for Improving Behavior Change Communication in Child Survival and Community Development Programs, Washington, D.C.: Food for the Hungry.

Family Health International. (2013). Examining the Influence of Providers on Contraceptive Uptake in Rwanda.

The Health Communication Capacity Collaborative. (2016) Factors Impacting the Effectiveness of Health Care Worker Behavior Change: A Literature Review. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs.

Hamid, S., & Stephenson, R. (2006). Provider and health facility influences on contraceptive adoption in urban Pakistan. International family planning perspectives, 71-78.

Kok, M.C., Broerse, J.E., Theobald, S., Ormel, H., Dieleman, M., & Taegtmeyer, M. (2017). Performance of community health workers: situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Human resources for health, 15(1), 59.

Tessema, G.A., Gomersall, J.S., Mahmood, M.A., & Laurence, C.O. (2016). Factors determining quality of care in family planning services in Africa: A systematic review of mixed evidence. PloS one, 11(11), e0165627.

Viswanathan, V., Seigerman, M., Manning, E., & Aysola, J. Examining Provider Bias In Health Care Through Implicit Bias Rounds, Health Affairs Blog, July 17, 2017.

Yadufashije, C., & Ndayizeye, A. The Factors of Under-Utilization of Family Planning Services by the Population of Gitega Health District in Burundi, in 2015 (September 21, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3040939 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3040939